In this talk, we are doing a deep dive into the audio market and the position of Spotify in it. You can find all the interviews in our Spotify archive.

- Introduction

- Who is Jeremy Deal?

- Who is Sleepwell?

- Drivers for the audio market

- New audio technology

- Digital payments

- Tiktok and Peleton

- Developments in music production

- Developments in podcasting

- Changes in monetization

- Difficulties in predicting the future of the streaming market

- The switch to digital

- Radio vs. on-demand

- Personalization

- Cracking the audio code

- Advertising money in radio and streaming

- Music royalties

- The role of labels & how they have to adapt

- Importance of labels

- Labels in the digital age

- Revenue shares around labels

- Actors in music & new dynamics

- Community Exclusive: Are labels replaceable?

- The podcast opportunities

- RSS technology

- Spotify's open access model

- Advertising podcasts

- Advertising content on YouTube & Spotify

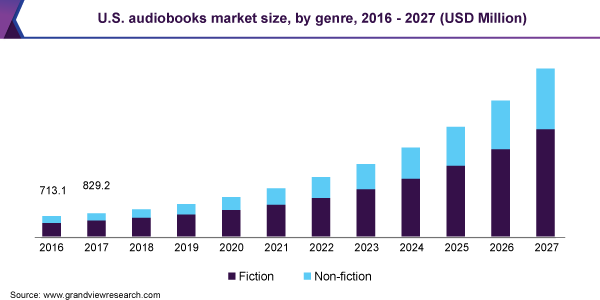

- Audiobooks

- Audio in the creator economy

- Closing thoughts

Introduction

[00:00:00] Tilman Versch: Hello audience! It’s great to have you back on my YouTube channel. Today, we will start to discuss the audio market as a whole and then funnel down to Spotify. I’m happy to welcome Jeremy Deal. Great to have you here Jeremy!

[00:00:16] Jeremy Deal: Great to be here!

Who is Jeremy Deal?

[00:00:18] Tilman Versch: You’re currently in Majorca so we can see your Finca or whatever it is in the background.

[00:00:24] Jeremy Deal: Yeah, a little family summer vacation. It’s nice to be here.

[00:00:29] Tilman Versch: That’s great.

[00:00:30] Jeremy Deal: Every holiday is a working holiday in this business.

[00:00:37] Tilman Versch: I hope you enjoy it a lot as well.

Who is Sleepwell?

[00:00:41] Tilman Versch: We also have Sleepwell Capital. You may know him from Twitter. In our episode he’s anonymous, so he will be shown with these nice two animals that are sleeping. How are you Sleepwell?

[00:00:53] Sleepwell Capital: Great! Thank you for having us, Tilman. We’re excited for today.

[00:00:57] Tilman Versch: It’s great to have you on. I think you both are invested in Spotify. Am I right?

[00:01:03] Sleepwell Capital: That’s correct.

[00:01:05] Jeremy Deal: Yes.

Drivers for the audio market

[00:01:06] Tilman Versch: So, we’ve done a disclosure with this. I’m happy to start now with our conversation. Let’s start with the whole audio option because I think in order to understand Spotify, we have to understand the audio market as a whole. I have a list of things that are happening, that are widening the total addressable market of audio and music consumption. So, let’s brainstorm a bit about them. What are key drivers that increase the market or that have increased the market over the last five to ten years in your eyes?

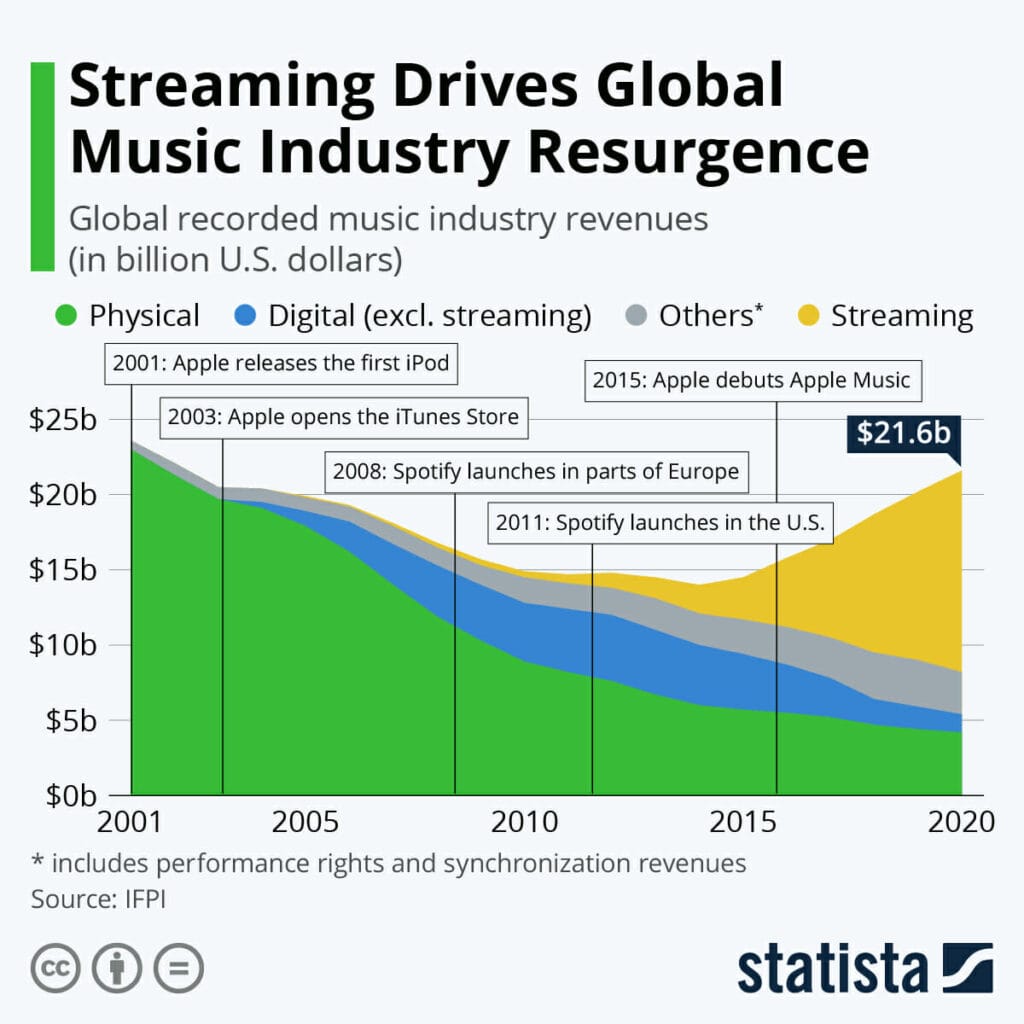

[00:01:43] Jeremy Deal: I can start by saying, just the introduction of streaming, finding a way like what Spotify initially did to resurrect the recorded music industry by finding a legal way to make unlimited streaming either out supported or available on a premium subscription basis. This was probably the most significant step that’s happened since the invention of the CD

[00:02:20] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah, absolutely. And on top of that, you have not only smartphones but sort of proliferation of devices, broadly speaking, where you can listen to music at basically any point in time. On top of that, throw the cherry on top when it comes to the hardware, which are your AirPods and the ease of just putting headphones on anywhere at any time. I think it’s resulting in just an explosion of audio consumption that we’ve already seen and stands to grow for a very long time.

[00:02:57] Jeremy Deal: I would add to that the cost of data has come down significantly in the last ten years. And so, while 10 years ago the average household would be a lot more price-sensitive to streaming audio but because the price has come down so much, it’s a lot easier just to stream something in your car and not worry about going over your monthly data plan.

I would add to that the cost of data has come down significantly in the last ten years. And so, while 10 years ago the average household would be a lot more price-sensitive to streaming audio.

Jeremy Deal

New audio technology

[00:03:27] Tilman Versch: What I would like to add and you also can see it in my background, if you studied it a bit. I’m sometimes like using my background to illustrate certain topics. You can see there the collection of headphones I have at home. I’m a bit of an audio nerd, so it’s not the natural headphone density you find in most households. I tried to collect all the headphones I find in my household. I have plenty of it since I get headphones with many devices. The interesting thing is you also get cableless. This is the cable of this pair of headphones that I connect to Bluetooth. Bluetooth enabled so much in hearing audio content. It’s so easy. You can do it while you’re doing the laundry or cleaning your house. You can hear it in high quality. Also, if you think about cars, what has changed there in your eyes?

[00:04:20] Sleepwell Capital: I think cars are a very interesting place to listen to music and audio in general because it’s still mostly just traditional radio. So, when it comes to the opportunity in terms of migrating from a legacy medium to an internet medium, car is basically one of the biggest places to go after. I fully expect that part of the market to be the last domino to fall and transition more fully into the internet.

[00:05:03] Jeremy Deal: Yeah, when you look at OEM. I mean, there are normally third parties that are supplying the hardware that goes into a radio or audio system in a car. A lot of these are built-in and the designs are decided many years before the car is produced. For example, you might be buying a 2021 Volkswagen, but the design of the audio may have been decided in the bill of materials two or three years ago. So, there’s always this lag, at least there has been traditional, in a lot of the audio systems inside new cars.

For example, you might be buying a 2021 Volkswagen, but the design of the audio may have been decided in the bill of materials two or three years ago. So, there’s always this lag, at least there has been traditionally, in a lot of the audio systems inside new cars.

Jeremy Deal

Most cars today do allow you to connect to the phone but besides that, it can be difficult to stream and like Sleep said, you just go right. It’s easy to default to the radio station because there is this process to connect to your phone when you get in the car so not every system is designed for assignments or just a very simple connection to your streaming account.

Yeah. When you look at OEM, I mean, there’s normally third parties that are supplying the hardware that goes into a radio or audio system in a car. A lot of these are built-in and the designs are decided many years or several years at least before the car is produced.

[00:06:10] Tilman Versch: Does either of you own a Sonos or another Bluetooth speaker?

[00:06:17] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah.

[00:06:18] Jeremy Deal: Yeah, at home.

[00:06:20] Tilman Versch: I think they were the first in the market when they launched five or ten years ago. It’s also a new format of playing and hearing music. I think it’s also quite interesting to know how you bought your Sonos or your headphones. I bought mine D2C, so they were cheaper than normal retail prices. There’s also something that drives consumption in the long term like the cost going down. What I also find interesting if you think about paying for streaming services, there’s still a huge population where our cash society is still persistent.

Digital payments

[00:07:01] Tilman Versch: Sleep, you have the background from Latin America. Is it becoming more and more banking and digital payments?

[00:07:07] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah, I think for emerging markets that’s definitely an important factor to consider. It’s kind of an obstacle when it comes to adoption. One reason why in many cases companies like Spotify partnered with local telecom companies that already have the user captive and already have some billing established with them. That’s another additional tailwind and specific to emerging markets as more and more people become either banked through the traditional means or through some of these fintech companies that are also growing a lot in these markets.

Tiktok and Peleton

[00:08:03] Tilman Versch: You both studied Tiktok and Peloton as well while you’re researching Spotify and music consumption patterns. What is happening there?

[00:08:15] Jeremy Deal: From a music or audio perspective, they’re just different forms, different avenues, different distribution channels for audio asset owners to be heard. It’s another channel. It’s another playlist. Again, these two companies, I have only looked at from the perspective of audio.

It’s obvious with Peloton that you want to get on a list or maybe listen to a podcast or music while you’re working out, but it’s just while you’re working out. Then with TikTok, you can see that when creators or when people put short-form videos up, they’ll use 10 or 15 seconds of a song in the background, or they’ll make a short dance video with a song or with a clip in the background. Where I’m less familiar with is how that actually works to trigger royalty stream. I know with Spotify the song must be streamed for at least 30 seconds to trigger a stream. And so, a lot of these clips that I’ve looked at on TikTok are less than 30 seconds. Maybe it’s also an avenue for an artist to get heard and hopefully one of their songs goes viral because somebody’s watching a TikTok video.

There’s a recent famous story of a skateboarder guy that is, I don’t know if he is homeless or almost is homeless or maybe he looks homeless or something, but he rides around Venice beach and he was holding an old radio. There was a song from the 70s, like a Fleetwood Mac song playing, it went viral all of a sudden.

So, a lot of kids that had never really heard Fleetwood Mac all of a sudden downloaded the song or went to listen to the song. It was the most listened-to song that day or something like that. I don’t know if Fleetwood Mac then gained a bunch of new audiences or new super fans, but it’s a way to get your song out there and get it played. So, I see it as just a different distribution channel.

[00:10:20] Tilman Versch: Do you have something to add Sleep?

[00:10:25] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah, exactly. I think those are all very valid points. I think the only point I want to make clear when it comes to TikTok and Spotify is they do sometimes get put together in the same bucket and some people may even consider them competitors. We can get more into that a little bit later but to me, they both are extremely good at discovery. That’s really one of their biggest value drivers when it comes to music. TikTok is well aware of that, obviously. Jeremy just gave a very good example of that and there are tons more.

That’s a big focus for the industry right now in terms of the impact that social media has and the importance of targeting and putting money and thought behind your social media strategy. I see them as complementary products. I don’t think TikTok is an audio-first product in any way. I don’t think anyone would say such a thing.

[00:11:30] Jeremy Deal: Right. I mean, if you are a manufacturer of some kind of packaged food, you’re going to probably try to sell that packaged food in gas stations. Those gas stations don’t really compete with a Costco or Walmart, but you probably want your product sold in Walmart grocery stores, the gas station, the mid-sized grocery store, and even online.

TikTok is just another channel. It’s a very different product. It’s not where people go specifically just to consume music, but it’s also a place where you’ll hear music. You hear audio everywhere. So, it’s just another distribution outlet for audio asset owners.

Developments in music production

[00:12:27] Tilman Versch: Another interesting point that I would see as a tailwind is the greater economy and also the ability to create is getting cheaper like in Tik Tok. There are also professional tools that are getting cheaper. Sleep, do you have any insights about this relating to the music production industry?

[00:12:37] Sleepwell Capital: Absolutely. I think there’s a couple of points to make to put what has happened in the past 20 years into perspective. If you think about what being an artist was like in the 1990s, you not only had to go to a recording studio, which was very expensive, you also had to hire musicians, sound engineers, producers, etcetera, you then also needed to find a way to manufacture these CDs and put them into stores. Obviously, all of this has changed meaningfully. There’s also the additional fact that the promotion and marketing part has changed a lot.

Nowadays, anyone can basically record their own album on their house by just setting up a home studio which is not really that expensive. Then you just go and upload your songs to all the different available streaming platforms via an independent distributor. You can basically market your songs using social media and things like that. So, the roles and barriers to entry have completely collapsed, which means at the same time there’s more competition than ever before. I think the latest stat we heard from Spotify is that there are over 50,000 songs being uploaded daily or something insane like that.

It’s millions of artists that are on the platform nowadays, but it also means it’s much harder to get heard. There are obviously different kinds of artists. Some of them may not see themselves as having a full-time job or a career in music, but in general, it’s good in terms of being a creator how easy it’s become to pursue your music as a passion or as a career, but at the same time, it’s become a lot more competitive. There’s a lot of additional effort and work that you have to put behind it.

Developments in podcasting

[00:14:48] Tilman Versch: Jeremy, you can underwrite this statement as getting less and less frictionless on the podcast sector as well because, I think, the reason why we are doing this interview here is I discovered your podcast where you’re talking about advertising and the opportunities that arise with Spotify. I will link that episode below. You also started a podcast, how easy or hard, was it?

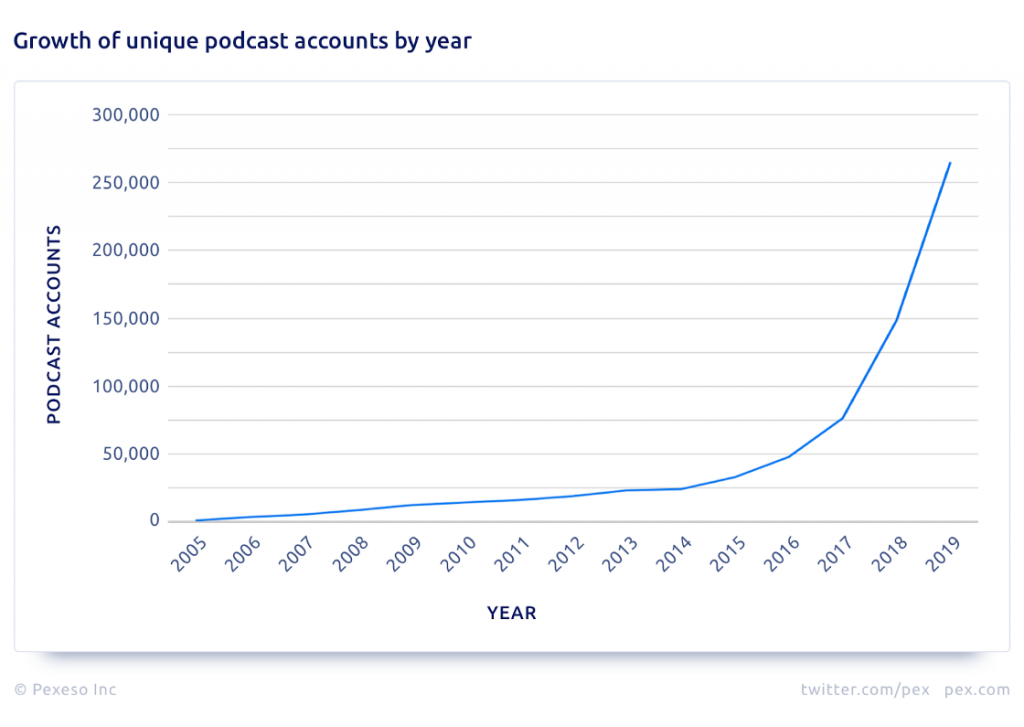

[00:15:11] Jeremy Deal: Oh, no. I didn’t start a podcast but I have been on a few just as an experiment. It’s a way to talk through different ideas during the pandemic. The podcast side is its own topic. The number of podcasts that are being created, back to what Sleep was saying, is significant. I think Spotify had 2.5 million or something as of last quarter, but I think this number is going to grow exponentially. I think that there’s no material cost to produce a podcast. And so, you’re just going to have anybody that’s interested, has a voice, has something to say, or could potentially attract an audience. There has been an explosion in content. It’s kind of the golden age of audio creation. And so, that will result in some really interesting ways to monetize that.

I think Spotify had 2.5 million or something as of last quarter, but I think this number is going to grow exponentially. There’s no almost cost to produce a podcast, and so you’re just going to have anybody who’s deeply interested in a topic with a voice and could potentially attract an audience. There has been an explosion in content. It’s kind of the golden age of audio creation and so that will result in some really interesting monetization.

Jeremy Deal

Changes in monetization

[00:16:23] Tilman Versch: I will show some charts relating to this. Another point I want to add that is also my bridge to the music industry. You mentioned Fleetwood Mac, that his song was kind of remastered. You also have Dolby Atmos for instance as technology or Sony 360. I will link a video below where you can hear the difference between the different sound settings because they offer a more joyful experience if you’re listening to music. At this point, do you have anything to add on the tailwind for audio in general?

[00:17:00] Jeremy Deal: We’re now seeing the number or just the sheer amount of audio coming to market. The technology to monetize audio is also very new and the way that we’re going about monetizing it is very different from the way other types of media have been monetized. There’s like a double opportunity here that’s happening really quickly, which is tons of audio coming out and it makes companies like Spotify valuable because they’re an aggregator.

The technology to monetize audio is also very new and the way that we’re going about monetizing it is very different from the way other types of media have been monetized.

Jeremy Deal

That’s not just it. It’s more about what they do with that information and how Spotify can be used as a tool to analyze content that’s coming to market. So not only from a consumer perspective to find what you’re looking for, but from the creator, perspective to make sure that you can actually get positive or negative feedback and potentially live off what you’re doing if you want to do it full time.

It’s more about what they do with that information and how Spotify can be used as a tool to analyze content that’s coming to market. So not only from a consumer perspective to find what you’re looking for, but from the creator, perspective to make sure that you can actually get positive or negative feedback and potentially live off what you’re doing if you want to do it full time.

Jeremy Deal

There’s just so much happening. We’re probably going to get into this later. It’s somewhat of a forgotten industry. It’s an industry in consumer tech. These are somewhat borrowed ideas from other podcasts that I can cite different research of different people I’ve listened to over the last couple of years of owning Spotify. It’s been an industry and a sector audio in general, where there hasn’t been a lot of venture capital. I think people just felt like streaming. Streaming was sort of the end. And now, it’s just about trying to grow subscriptions and move away from radio and moving the ad dollars over from radio to streaming. That’s definitely not right. We’re in the really early phases of, I think, an explosion in audio all around.

[00:19:20] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah, that’s an extremely good point, Jeremy. I think when it comes to, especially my thesis on Spotify and just the music industry and audio in general, I think there’s the fact that I have a strong belief that this industry is going to be much bigger than most people imagine. In many ways, it’s very much related to what you mentioned in terms of monetization. On average, people listen to something like four hours of audio per day, half of that being on the radio which is still yet to migrate over to the internet. It’s billions and billions of people that the market has an opportunity to attract.

Finally, I think the other point to make which Daniel Ek has talked about at different points in time is the monetization gap between music, audio, and the other media forms like video, video games, and social media. There is a need to work to close that gap. Probably not completely because it’s still a more passive kind of media consumption, but I would argue the difference is way too high at the moment.

[00:20:41] Jeremy Deal: That’s right. I put this in my half-year letter that the recorded music industry’s global value is something like $31 billion. That’s in revenue. I know that doesn’t include all pieces of audio in general, but to think that even after the enablement of streaming, that it’s so small. I cited in there that it’s the size of the global banana industry. Podcasting is even worse.

Just to go back to audio and Sleep’s point, I read a statistic. I don’t know how accurate any of these statistics are but something like the average adult on earth consumes 3.8 hours a day of audio. That could just be you in the store when there’s music playing or you’re in an elevator and there’s elevator music or you’re actually listening to audio of some kind including TV or whatnot. But 3.8 hours a day and you have the recorded side only worth $31 billion more or less.

The former economist of Spotify, who has a blog, put that stat out. He goes through a process of recalculating what the actual value is versus a lot of the values that are put out there. I also made the comparison of podcasting ad revenue of somewhere between $800 million and $1 billion for this year or maybe last year is the size of the disposable plastic lighter industry. If you think about just how much engagement there is with audio, I think it’s very obvious that there’s a very big gap to be filled here. The addressable market should be much bigger and will be much bigger.

Difficulties in predicting the future of the streaming market

[00:22:43] Tilman Versch: What do you estimate this market could be worth in 2030 for instance?

[00:22:53] Jeremy Deal: I haven’t gone down that path. Sleep, you may have gone down that path. I haven’t thought about it too much because I think that it’s just too early to. I don’t know how it’s going to unfold, and I thought about it like if you looked at Microsoft back in the early 90s and tried to come up with the addressable market or you tried 10 years ago to put your finger on what the streaming addressable market would be for Netflix, the sell-side would say only a few billion. We’ll never know everything.

I don’t know how it’s going to unfold, and I thought about it like if you looked at Microsoft back in the early 90s and tried to come up with the addressable market or you tried 10 years ago to put your finger on what the streaming addressable market would be for Netflix, the sell-side would say only a few billion.

When these big transitions happen, they happen so fast and with so much strength that tons of new business models are created on top. That’s where the addressable market just explodes and that’s why it’s hard to imagine. I also made the point in my half-year letter that the e-commerce space is still creating.

There are still new business models coming out of e-commerce all the time and I made the point that Shopify has added something like $100 billion in value, just in the last three years. I don’t think that was ever a part of anyone’s forecast of the addressable market or the outskirts of the addressable market that would be created because of e-commerce.

There are still new business models coming out of e-commerce all the time and I made the point that Shopify has added something like $100 billion in value, just in the last three years. I don’t think that was ever a part of anyone’s forecast of the addressable market or the outskirts of the addressable market that would be created because of e-commerce.

[00:24:30] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah. It’s one of those things where you can’t really put a number to it. There are definitely people that have tried. I’ve seen numbers thrown around the area of $200 to $300 billion in 2030.

To Jeremy’s point, a lot of these markets are being created in front of us right now. There’s no comparison you can make to it. Jeremy made a good comparison with Microsoft. The other one I’d like to go back to is when Google IPO, a lot of people thought the opportunity they were going after was the newspaper advertising business. Imagine how wrong you were if that was what you were focusing on when in fact it was much bigger than that. It was really a global opportunity that was also much bigger than anything that existed before because it was a completely new media format. It had a much higher ad efficiency and things like that. I think that’s an interesting comparison to make as well.

[00:25:38] Jeremy Deal: What I see people try to do is calculate the addressable market of the subscription side of music. So, how many subscribers could Spotify have someday, how many Apple subscribers will there be and how much will they pay. They multiply that together and discount it and say that’s the addressable market. That’s completely wrong.

What I see people try to do is calculate the addressable market of the subscription side of music. So, how many subscribers could Spotify have someday, how many Apple subscribers will there be and how much will they pay. They multiply that together and discount it and say that’s the addressable market. That’s completely wrong.

Jeremy Deal

That’s almost the opposite thesis of what I think we’re talking about here as far as understanding what’s possible with music and how to think about the addressable market. The fee you pay every month, let’s say in 20 years you’re paying something like $25 a month for a premium Spotify subscription and then they say they have a billion subscribers or something. That’s great but the real opportunity is in the addressable market that comes out of the tools and the models that are built on top of these rails that Spotify has created.

[00:26:44] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah, it will be a lot of, I think, incremental revenue that will sit on top of that base subscription when you think about things like monetizing super fans and things of that nature. It’s just going to grow the pipe much more.

The switch to digital

[00:26:58] Tilman Versch: In which part of the inning for switching to digital are we in the audio space?

[00:27:02] Sleepwell Capital: I mean, it’s definitely early. I would probably say the third inning maybe.

[00:27:10] Jeremy Deal: Yeah, I would agree with that. People are aware of streaming. I was just in an emerging market a couple of weeks ago. I met this little kid that I was sitting next to. He’s probably five or six. He was streaming Spotify. It was Spotify for kids. It was on this iPad that was sitting inside of what looked like a bulletproof case so it could be thrown across the room. It was in his language. I just thought, “Wow!” The awareness is there. However, I would be willing to bet when that kid gets into a random car with his grandma or his aunt or whatever to go somewhere that there’s radio in the car going on. Or when he’s at school or at the supermarket, it’s not necessarily always streaming happening. It’s hard to say. People are aware of it but just haven’t fully converted.

[00:28:17] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah, I mean, if you look at the numbers, there are roughly 440 million subscriptions when it comes to music. There are 3.5 billion smartphones, a number that is probably going to double in the next 10 years. Music is probably the most universal media form because it’s pretty well known. Literally, everybody listens to music now. What does the end state look like? It’s obviously hard to say but directionally, Daniel Ek has talked about the opportunity left being probably seven may be as high as 15 times of where we are now. It’s obviously going to be a combination of subscriptions with ads supported and maybe new formats that we haven’t really thought about yet. It’s clearly much bigger than where we are now so the tailwinds are very strong.

Radio vs. on-demand

[00:29:12] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned the radio market. How much better can a digital experience be instead of hearing radio?

[00:29:20] Jeremy Deal: Well, on-demand is on-demand. Instead of listening to what they want you to listen to, you’re always listening to what you want to listen to. That’s probably the fundamental difference. It’s the same with Smart TVs and streaming TV content. You don’t wait until the new episode starts at 6 pm. You just kind of watch when you want. It’s the same with audio. That’s just on the entertainment side. There’s another side of this around the search and discovery of data inside podcasts, audiobooks, and things like that that will be layered on top. But just on the music side or I guess in general, it’s just on demand. That kind of experience just can’t be replaced.

Discover the Plus Investing community 👋🏻

Hey there!

Discover my Plus community! The community is great for passionate, professional investors.

Here, you can meet investors, share ideas, and join in-person events. We also support you in starting and scaling your fund.

[00:30:20] Sleepwell Capital: It’s vastly superior to whatever linear has been offering for the past 80 years or something. In many ways, it’s similar to what’s happening with video, where I think audio is a little bit different. Companies like Spotify can make a big difference and have an advantage when it comes to personalization. That’s another feature that I think OnDemand is going to be a much better experience than linear because if you’re using a platform that knows you intimately well and knows exactly what you want to listen to at different points in time, it’s not only about selecting that specific episode or artist that you want to go to. Sometimes you’re just going in and just put on what you think you want to listen to because you trust this platform to know that. I think that’s what they’re striving for really.

Personalization

[00:31:20] Jeremy Deal: Personalization is really important, and I think we’re also in the really early innings of understanding how important that is as more and more content is put out there and produced, whether it’s talk or music, the more important that discoverability is. The winners are going to be the companies and we hope Spotify is that or one of them. They can build the correct personality profiles on you that continue to build and grow on top. So, what we, in a perfect world, would love to have happen is Spotify to have those capabilities, similar to how you think about Google search but for search and audio.

Personalization is really important, and I think we’re also in the really early innings of understanding how important that is as more and more content is put out there and produced, whether it’s talk or music, the more important that discoverability is. The winners are going to be the companies and we hope Spotify is that or one of them. They can build the correct personality profiles on you that continue to build and grow on top. So, what we, in a perfect world, would love to have happen is Spotify to have those capabilities, similar to how you think about Google search but for search and audio.

Jeremy Deal

Why is there really no competition for Google search is because their algorithms learned on top of each other? So, every time someone uses it, it gets better. As people use it, it exponentially gets better. It’s not just somebody tweaking an algorithm in the background. The idea in audio is that the more people use a platform like Spotify, the more the algorithm can learn and grow based on your personality and understand what you might be interested in hearing or researching based on, like Sleep is saying, what time of the day it is for you. Apparently, if you’re going through a breakup, they suggest breakup music. So, they know you’ve gone through a breakup or you’re at the gym or traveling and they suggest appropriate music.

The idea with audio is that the more people using a platform like Spotify, the more the algorithm can learn and grow based on your personality and understand what you might be interested in hearing.

Jeremy Deal

So, as that grows, it’s moving away from just simply streaming but into the very uniqueness of the search and discovery features that is very much unique to the individual companies. TikTok has a discovery feature and a way to grow. I’m sure we’ll probably go into this a little further on social media and what they do with that information.

So, as that grows, it’s moving away from just simply streaming but into the very uniqueness of the search and discovery features

Jeremy Deal

Search and discovery features of the different companies vary because the companies themselves are fundamentally really different. These are the points of differentiation that create more value at companies like Spotify in particular because of the personality profiles that I think they’re building and focused on that will become more and more interesting and relevant as time goes on.

Cracking the audio code

[00:34:08] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned the newspaper industry. Will we see radio stations and radio companies going the same direction as the newspaper industry?

[00:34:17] Sleepwell Capital: I think we will. It’s going to take time because certain habits are very hard to change. Jeremy mentioned some of the things that come pre-built in the car and things of that nature. Obviously, it also skews to an older demographic that has basically spent their entire lives listening to radios. It’s not going to happen overnight, but there’s definitely going to be a 10-to-20-year tailwind. It’s just going to be grinding along every year and taking market share from linear to on demand.

[00:34:57] Jeremy Deal: If you look at what happened, there probably will be something that causes it to move forward really quickly. Who would have thought that the pandemic would have led to TV streaming all this content moving from linear to streaming overnight? That was not slated originally to be moved over so quickly. HBO maybe had an app but two years ago the executives probably never would have thought that it would all just instantly move over. The pandemic eliminated sports. And so, the cord-cutting just became more accelerated. That then accelerated the move of mainstream content or forced the hand to move content over. So, now we’re in the process of the advertisers now following and trying to play catch-up to where the eyeballs of the consumers are.

There could be something like that, I would imagine in audio, where it’s just a slow move and then we wake up one day and there’s one event or a series of events and hopefully it’s not something like a pandemic, but it could just be the creation or evolution of technology. What I think it is going to be is something around cracking the social media code in audio. I think once that happens, which does feel like we’re closer and closer to that than we’ve ever been, once that social audio code is cracked then that could potentially move people much faster away from radio and onto streaming.

Advertising money in radio and streaming

[00:36:41] Tilman Versch: Are there any other factors involved in the cracking of this audio code? You mentioned the newer car generations that have computers that can easily unlock streaming. Are there any other drivers in your mind that would encourage people to become more digital or incentivize them to stop listening to the radio?

[00:37:00] Sleepwell Capital: I think the advertising part is interesting because it’s probably not as fast as some people would have imagined, but it’s obviously a much better ad targeting tool than with radio. It’s much more efficient. You can measure exactly what your ROI is, which is much better than at least traditional radio. You’re targeting the exact people that you want to target. As more and more of those ad dollars move over to podcasting and streaming audio in general, that probably is an additional driver from linear to on-demand.

[00:37:48] Jeremy Deal: That’s a great point because the light ones, the oxygen is sucked out of that. I mean, it’s an advertising business so things will change and the radio companies will probably shrink as their ad dollars go away.

[00:38:05] Sleepwell Capital: It’s going to bring better creators to podcasting as well as the market gets bigger. Naturally, right?

[00:38:13] Jeremy Deal: Just from the consumer side. I don’t know how many advertisements you’re listening to in an hour of radio, but it’s just unbearable. I would guess 40% to 50% of an hour. Sleep, do you know what percentage?

[00:38:33] Sleepwell Capital: I don’t know if it’s that high but it’s definitely over a quarter.

[00:38:39] Jeremy Deal: Yeah. And the ad loads are much lower in streaming, generally, because of the targeting. So, it’s a better experience for the consumer with just that alone. That’s just on the free side. On the premium side, it’s superior, from experience on the consumer side. There’s just so many reasons to move over to streaming. I cringe when I get in my rental car and there’s radio playing. I just cringe. I can’t tell you just how quickly I try to connect my phone to the Bluetooth. Then again, I’ve got a big bet on Spotify so that’s my subconscious talking.

Music royalties

[00:39:49] Tilman Versch: Let’s move on with a question that came from Twitter regarding the music industry and the royalties. Sleep, there was this question, if radio stations have to pay for music playing, why wouldn’t they make use of streaming if they don’t have to pay?

[00:40:11] Sleepwell Capital: I think the question was related to how much radio pays in terms of royalties to the rights holders versus streaming. I think it’s important to set the stage here a little bit. I don’t want to get too technical here but when it comes to music it’s obviously a very complex subject, especially on the legal aspect of it.

Broadly speaking, when you think about a song, we’re basically talking about two separate copyrights. You have the composition, which is literally the musical sheet where you have the lyrics and the melodies, and you can give it to a professional musician, and they’ll just play that exact song that someone wrote. That’s intellectual property but that’s one type of intellectual property. The other one is called the master recording, which is the actual recording that you hear of a song. When the artist goes into the studio and records that song, there’s one version of that that goes out and is played everywhere on the radio, on Spotify, etcetera. Those are the two separate IPs that are associated with a song.

In the United States, there’s a bunch of history related to this but for one reason or another, it happens that radio stations only pay the composition royalty, which is also known as publishing. They have always argued that what they are doing is promoting the song so they shouldn’t have to pay the other side of the rights, which are the master. There’s been a lot of battle back and forth on this and it’s been like that forever.

In other parts of the world, the radio will pay for both sides of that IP. In general, radio, even those radio that does pay both of those rights, the total payout is much lower than a Spotify would, for example. This is because they also have non-music-related content like talk shows, sports, news, and things of that nature. They’ve been able to negotiate those lower payouts in large part because not all that they’re showing is music-related. You also don’t get to pick what music is played.

When Spotify started negotiating with the labels, one of the biggest pushbacks from the labels was that they were providing such a superior product in terms of being able to pick exactly what you wanted to listen to. That immense value meant that the rights holders should be getting a much higher payout than they otherwise would if you would just go to a pandora and put on a station. This is known as interactive streaming in the industry and legal jargon. There’s a lot of complexities to the legal aspects behind all this but it basically results in Spotify paying out roughly 65% of their revenues out to the rights holders, which includes many intermediaries and it’s both the master recording side as well as the publishing side. You have a bunch of people that are involved in between such as the collecting agencies, managers, labels, publishers, and obviously the artists. That’s how we got to where we are now and why those two are a little bit different.

[00:44:40] Jeremy Deal: I’ll just add that there’s always confusion around the artist and how much they get out of that 65% to 70%. If you are owned by a record label, if you are a famous musician who has traded your master for a collaboration with a label, you’re owned by the label. The label determines what percentage you get. I believe it’s somewhere around 10% of what they receive they give to the artist on average.

If the artist was completely independent and completely detached or unconnected to a label, completely self-published, which probably isn’t realistic for someone famous or somebody that’s really big, but let’s just say there was no intermediary involved, you would be getting maybe 6 times the payout than what you are getting now. That’s meaningful. It’s not necessarily up to Spotify. Spotify is not determining how much the artist gets. They don’t determine how much YouTube gets per stream. I don’t know if it’s Atlantic records or whoever it is. That’s who determines it. It’s not Daniel Ek. “Oh, okay. I think we can maybe afford them a little bit more/a little bit less this year.”

From the streamer’s perspective, they’re getting 65% to 70%, which I think is a fair margin. I don’t see that changing dramatically, but how that plays out with who gets what within that 65% will probably change over time. The value is less interesting from an artist’s perspective to fight over that. Let’s say you even kept all of that, right. Let’s just go back to self-publishing or let’s say in a dream world you were with one of the big labels and you got to keep 100% of your streaming revenue. Well, is that really that interesting? No, not really. What we’re really playing for here is an explosion in the addressable market of audio and connecting with your super fans and building your brand and monetizing your brand in ways that were never possible before. So, streaming in a way becomes your CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) in a strange way.

So, it’s just sort of, “Okay, great. We have a positive CAC.” That’s nice. We have something that people can hold on to but it’s just a mechanism to start to be able to build and identify your super fans to then go monetize in totally new ways. I think this is where radio falls short because once a musician realizes they can make 10x or 20x more than they’ve ever made before by using the discovery tools. Whether it’s advertising, whether it’s helping funnel sales of different things or any new item that can be created to support the artist. The sky is the limit. I think this goes way beyond concerts.

The stream is immaterial at that point. It’s just like, “Yeah, whatever. We got a cheque in the mail.” I mean, think about these actors that still get paid a few pennies every time an episode airs of something they did in the mid-90s, and it all adds up to something per month. That’s really not necessarily how they’re all looking to expand that, to go from making five cents per rerun to 30 cents per rerun. I mean, their earning power is in their brand and how recognizable they are and how famous they are, and whatever they can decide to do with that. I think it’s similar to the future of musicians and podcasters and talk radio as well. The stream is just how we got started.

The role of labels & how they have to adapt

[00:49:00] Tilman Versch: Let’s move on. You already built the bridge to the music market and their investors. You talked a lot about labels. What functions do labels play in the music industry and how has it changed over time?

[00:49:16] Sleepwell Capital: I briefly touched on this when I talked about being an artist 20 years ago versus today, right. Basically, every traditional function that a label was doing in the 1990s, you can replicate on your own today in some form or another at very low costs.

Now, that doesn’t mean at all that the labels have lost their place in the industry. Actually, the way that I like to think about it is, it’s one of those first-order versus second order thinking. The first-order way of thinking is, “Oh, wow.” It’s the easiest time in history to put out music but the consequence of that is that you have hundreds of thousands of artists nowadays. So, you need someone to help you stand out, especially if you want to be a superstar. That’s when the labels really come in.

When you think about the different things that the labels do, some people think that they just give you an advance. They’re kind of capital providers and that’s where their role stops, but I would argue that’s probably the least meaningful part of the value that they’re adding. Money is a commodity, right. If that’s all that they were doing, you would just turn around and go to a bank or an investment company and ask them for something similar. Obviously, they are the experts on calculating the risks that they’re taking when they’re financing new artists. It’s a very risky endeavor. I forget exactly what the statistic is, but it’s probably 5% to 10% of artists that actually ever become profitable for the labels. All the other ones, they lose money on. Those more than makeup for the rest in a similar way to a venture capital model.

Once an artist is signed, there are a lot more things that start taking place after the artist is brought onto the label. They’ve come in with a project in mind and a collection of songs but they have to start taking those songs and actually come up with a finalized commercial product. It takes a lot of people to get involved in that. Not only when it comes to going to the studio and producing the songs and the albums but there’s a lot of concepts that go into each artist when it comes to their art, their brand, all the videos that are associated to basically build the brand.

After these songs or records are put out into the world, the label is in the best position to push those songs and get them to the right listeners on a global basis. If you’re an artist, you want to be heard by as many people as you can. It’s really hard to do that if you don’t have enough money to promote your music, but also kind of the logistical and the network of people that are required to be listened to.

For example, I could be putting out a song tomorrow. Let’s say I live in Miami and I’m going after my fans in Miami, but what if my song happens to be really popular in Germany where you are Tilman. If I’m signed to a label, the label is going to just call their local office and start pushing for radio time, playlists. I’m going to get interviews with the local TV, newspapers, blogs, and things like that. So, it’s very logistical. There’s a ton of work that goes behind a musical project of that nature. If you think about it, that’s only the sound recording aspect.

On top of that, you have things like merchandising and touring and all those other sorts of revenue streams that are part of the job that are also super important. At the end of the day, most artists just want to be spending time either making music, recording music or playing music. They don’t want to be having the headaches of having to deal with lawyers and business managers. That’s not really their focus the majority of the time.

[00:54:39] Jeremy Deal: I would also add that there are more and more options, more places, and more ways to distribute music now than ever like we are kind of hitting on earlier. You’re going to have to be on Spotify. You’re going to have to be on YouTube. And then, you’re going to have to have some strategy to try to get your music attached to different advertisements, branding, commercials, or peloton. If you look at the modern music labels, which are more like a representative or something, like a talent agent maybe for actors. Even that is not easy. I wouldn’t know what to do. Let’s say I had a band and I know there are all these different ways I could potentially build a fan base, but I wouldn’t know where to begin. And so, the expertise, whether it’s the big label or even the more “modern” labels like Believe in France, it’s still a lot of work.

I would also add that there’s more and more options, more places, and more ways to distribute music now than ever like we are kind of hitting on earlier. You’re going to have to be on Spotify. You’re going to have to be on YouTube.

Jeremy Deal

There’s some economics that are deserved there. It may not be owning of the master. Maybe it is. I think on the low end, it’s 10% of revenue. On the high end, it’s whatever is negotiated. I don’t think these 360 deals are being done anymore but it’s quite a lot of work. You’re seeing a lot of money going into music rolling out, music catalogs, and music. You see even Oaktree is financing. There are several bigger private equity funds going into this and rolling up music rights. It’s not just because multiples are high in the market and they’re hoping to go public, it’s really because there’s never been a bigger spread between what people earned in general and what is really possible.

You may have an artist who can’t tour anymore and they’re kind of near the end of their career, or maybe they have died, or maybe the heirs own it, or maybe they just can’t tour anymore. It makes sense to sell for some multiple of revenue but the reason that somebody else can buy it and make money with it is that they can figure out how to. It’s like the early days of the internet. You could figure out how to get on. You could rank on Google or you’d pay somebody to help you rank on Google Search. It’s kind of like that. Only imagine a Google Search situation across many different avenues.

It’s a very rapidly evolving space as far as monetization is concerned. You’re going to need somebody in the middle if you’re going to be serious about your work. I’ve come around to believe that there’s going to be a different deal for different artists. There’s going to be rappers that come out and they self-publish at the beginning, but they’re going to need to hire somebody to help them move along because you can’t build a multi-million-euro brand just in your garage. You can get started and it puts you in a much better negotiating position if you already have had millions of people listening and loving your music, but you still need help. It’s not just somebody to book your tour, it’s more than that. There’s value for even the old labels, but I’m sure that they are pivoting and changing very rapidly internally as well. The old way that they used to make money has evolved. They’re no longer stamping CDs anymore, but that doesn’t mean that they are melting ice cubes by any means.

[00:58:25] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah. It’s incredible how they’ve been able to adapt to all these changes that have taken place. If you think about how devastating it was for the industry in the mid to late 2000s when piracy hit, it’s pretty incredible how they were able to navigate through that.

Adding on top of what Jeremy was saying, it’s pretty instructive to just look at the data, especially being a superstar, because I think it’s important to separate different kinds of artists and not all artists want to be superstars, but if you want to be a superstar, the top 10%, top 20%, they are all signed to a label.

Take a look, for example, at Taylor Swift, who has been one of the most vocal. She had this whole drama with her masters and her previous label. You would think she’s the first artist or main artist that would kind of go out and strike on her own, but she turned around and she signed with Universal. So, that already by itself tells you the fact that Universal is adding a lot of value to her career and to her life in general. Now, she obviously got a really good deal. She’s going to own her masters, etcetera. But, she’s still with a label.

Going back to that comment I just said in terms of the different aspirations that our artists have; the independent market is probably very appropriate for an artist that may not want to be a global superstar and they just want to do their own thing like what they call do-it-yourself route. Maybe have three or four cities where they have most of their fan bases. Thanks to streaming and touring, they can probably make a decent living out of something like that. I think that’s actually another interesting opportunity for Spotify to give the appropriate tools to those kinds of artists in the future.

Follow us

Importance of labels

[01:00:45] Tilman Versch: How important are labels for organizing the production of high-quality music and organizing division of labor in the music production market?

[01:01:00] Sleepwell Capital: When you think about superstars, like just pop music in general. You can probably expand that to other genres that have basically become very global nowadays, like hip-hop, reggaeton, and things like that. The top 50 or however you want to segregate that, the majority of that is signed on to a major label. It’s probably not only related to the quality of the products that these recordings are going through but much more related to the brand and the capabilities of putting out that record on a global basis which takes a lot of logistical know-how, network, a lot of money.

There’s an image that’s always associated with most of these superstars. That image takes also a lot of time, effort, and money to build, not to mention how much something like Dua Lipa tour would cost. These are very high-budget and complex organizations that take care of things of this nature. So, again, in that part of the market, the labels are very important.

Also, the digital tools grow and explode. You’re going to need more and more help.

Jeremy Deal

[01:02:43] Jeremy Deal: Also, the digital tools grow and explode. You’re going to need more and more help. I mean, I could see a whole team dedicated to a superstar just focused on tools of the top three DSPs because the sky’s the limit on a lot. I mean, just looking at the top 5 or 10 Spotify tools that exist just today and those have evolved enormously just in the last year. I can’t imagine the combination of things you could do. It’s just whatever you can create and dream of. I could see somebody at a label whose idea is to dream up ways to promote XYZ person and it starts with identifying the superfan and the traits of the superfan, where they are, what other things they listen to, how they listen to it.

Let’s say you could find information like the demographic of the superfan. Just name a demographic of a person in this part of the world and they generally listen to the music before they go to bed, or when you’re in the gym. You could organize all kinds of promotional tools around that knowledge. Whether it’s deciding to, I don’t know, hey, this is some up-and-coming artist. Everybody listens to his music at the gym. For his superfans, he’s going to talk about his favorite workout. And then, maybe even saying something, or maybe we should have him/her play some music at home and have everybody vote on what they liked. Ask-me-anything scenarios. It’s whatever you can think of. And so, as these tools grow, there are more things that come up as opportunities.

Demographic of a person in this part of the world and they generally listen to the music before they go to bed, or when you’re in the gym. You could organize all kinds of promotional tools around that knowledge. Whether it’s deciding to, I don’t know, hey, this is some up-and-coming artist. Everybody listens to his music at the gym. For his superfans, he’s going to talk about his favorite workout. And then, maybe even saying something, or maybe we should have him/her play some music at home and have everybody vote on what they liked. Ask-me-anything scenarios. It’s whatever you can think of. And so, as these tools grow, there are more things that come up as opportunities.

Jeremy Deal

They could think of more opportunities for this up-and-coming artist, like selling gym gear. You hear about some of the big rappers, they own a stake in Vitamin Water. I forget which rapper. He had a 10% or 20% stake in Vitamin Water and when it was sold to Coke, he made hundreds of millions. Every now and then, these people get involved but imagine that times a thousand because there’s something that you could be a part of as an artist like a promotional deal that you never would have been able to think of before because it didn’t require you to be the biggest and the best, or maybe it is for the biggest stars. Instead of just being involved with Vitamin Water, it’s involved with 20 or 30 other things that are unrelated and don’t compete with each other. So, as these ideas snowball and grow, the tools can be used to make so much money with your brand.

It’s all about building the brand equity. Right now, the equity of most music brands is zero. Everybody’s focused on the streams. The streams are the only thing that’s really been there before, but the stream is not what’s interesting.

Jeremy Deal

It’s all about building the brand equity. Right now, the equity of these brands is just zero. Everybody’s focused on the streams. The streams are the only thing that’s really been there before, but the stream is not what’s interesting. The stream is not really what we’re talking about. I think as these tools to unlock the industry evolve, I think the hiring profiles at the big music labels will be more tech-type people or ad tech. The types of people that they hire will evolve, but it’s like McDonald’s becoming healthier over the years. They just adapt to the environment.

Labels in the digital age

[01:06:17] Tilman Versch: Do you also see labels in the third or early innings of the transformation to digital? What is your take on the digital state of labels?

[01:06:30] Jeremy Deal: I think they’re very aware. They were shareholders of Spotify. They were part of the original group that sat around a table, as far as I understand it. Sleep, you may know more about this. But the way I’ve heard this story told is that Daniel Ek got everybody in a room, and they agreed on a deal. They were all partners in this which is part of the problem now of decoupling away from these original partners as far as the original economics. That’s another topic, but I think that they are very aware because their revenue had significantly reduced. They were willing to try anything, the way I understood it. I mean they were getting crushed by pirating and they said, “Okay. Well, let’s give this a shot.” And then it worked, so they know what’s there. They understand what’s happening. And from the interviews we do and conduct with people in the industry, Spotify and all the DSPs are also really involved with the music labels and meet with them sometimes every day. They have a group at Spotify, the way I understand it at least, that is assigned to different people at the different labels, and they just have open communication. Their job is just that. So, I would imagine they’re very much aware of what’s happening.

[01:08:01] Sleepwell Capital: Yeah. I mean it’s interesting. I suggest anyone who has an interest in Spotify, the labels, or just the music industry in general, take a look at the presentation that Pershing Square Tontine put out on Universal Music. Obviously, we saw that announcement a couple of weeks ago. I mean, the whole investment thesis for the company is based on streaming. That’s their biggest selling point and just going digital in general.

I think as it stands right now, digital which includes streaming, ad-supported, and things like TikTok, Facebook, and Peloton, etcetera, are probably around 60% of a label’s revenue today, with the remaining 40% being physical sales and things like merchandising and other revenues. They get a little bit from touring depending on the contracts that they have with certain artists, but the majority of it is already coming from streaming. It also happens to be the highest margin business. So, that’s their biggest focus going forward.

Revenue shares around labels

[01:09:22] Tilman Versch: Here we have the chart of the revenue shares.

[01:09:25] Sleepwell Capital: Yes exactly. That’s the global recorded music, right? That’s 50% of the revenues are basically coming from streaming today. I think in the United States, it’s actually closer to 80%, but you still have a pretty, maybe not fair to call it too significant, but physical has actually leveled off a little bit recently, but it’s not at such a fast decline as it used to be. If you look under the hood, things like vinyl are growing at double digits, if I recall it correctly. Then, you have countries like Japan and Germany, where people are still very big on physical.

[01:10:20] Tilman Versch: People still buy CDs in Japan.

[01:10:22] Jeremy Deal: Yeah. I’ve read that too. There are a lot of things happening. Just zooming out, it’s easy to be critical of the labels for being big and slow but I wrote out a timeline of just some of the Spotify tools that I’ve been interested in since I’ve owned the stock from late 2018 to early 2019. A lot of the stuff that they’re doing now is very new and you can’t expect full complete adoption overnight. It’s all very cutting edge. I think it’s important. It shows the direction of where things are going, and it’ll be adopted. I think you’ll see the music industry; you’ll see the big labels adopt more and spend money for these tools but they’re all relatively new. There always were some kinds of promotional tools out there.

The first promotional tool was just the playlist as far as I know. Once that recommendation music, that engine, was developed, it gave some opportunity to put some music ahead of others, but it’s only been recent that the real tools have come about. I think that’s what’s growing exponentially and that’s why I’m excited about the company. What people don’t realize is how fast that’s developing. What we could see is the music industry paying, rightfully so, to spend more money to grow in different ways that just hasn’t happened before outside of streaming.

Actors in music & new dynamics

[01:12:06] Tilman Versch: With the returning growth we see on this chart, I have the feeling that there are also some new battlers opening in the music industry and there are some actors coming to the playing field like Pershing Square that you already mentioned as investors in music. It hasn’t been there before. We already mentioned the topic of songwriters versus Spotify, versus labels, or musicians versus Spotify, versus labels. The percentage that goes to the musicians is a battlefield. We also have the streaming platforms versus labels. What are the power dynamics you’re observing and what is your opinion on them as part of the new coming growth? What kind of new actors have come to the music industry playing field?

[01:12:56] Sleepwell Capital: I would say the biggest new actor that we’ve seen as a result of streaming is what is known as a distributor. Jeremy mentioned one a little bit earlier, which is Believe, that actually just IPO’d in France. Some of the other more popular ones are CD Baby and TuneCore which is owned by Believe and Distrokid, but there’s a lot. This is especially relevant for independent artists that when you have a recorded song ready for commercial use, you’re not going to go out and upload it manually into Spotify, YouTube, Apple music because there’s hundreds of these DSPs. As an artist, you need maximum exposure.

So, what you do is you hire a distributor, also known as an aggregator and you pay them somewhere around 10% of your revenue and they basically take care of putting out your music in all the relevant digital channels. They also help you with collecting the royalties, etcetera. That’s the biggest sort of new player that we’ve seen as a result of streaming. Again, it’s much more related to the independent part of the market, which is around a quarter of the market with the other three quarters being part of the labels.

[01:14:47] Jeremy Deal: I think the social piece of music is really early and may not be necessarily an obvious new player, but I think as soon as the wheel starts turning on music becoming more social, just audio in general becoming more social, that audio code and cracking that audio code, there’s going to be new and existing players that become much more important. There’s probably going to be others that are less important. So, social and finding a way. Is there anybody that can find new ways to help build a brand of an artist are going to increase in value and become more important. Those that don’t reduce those frictions will become less important.

Community Exclusive: Are labels replaceable?

[01:15:47] Tilman Versch: So, as a closing question for the music and the labels part, before moving on to podcast as the next audio opportunity. Please give a yes or no answer to this question. Are the labels becoming replaceable?

The podcast opportunities

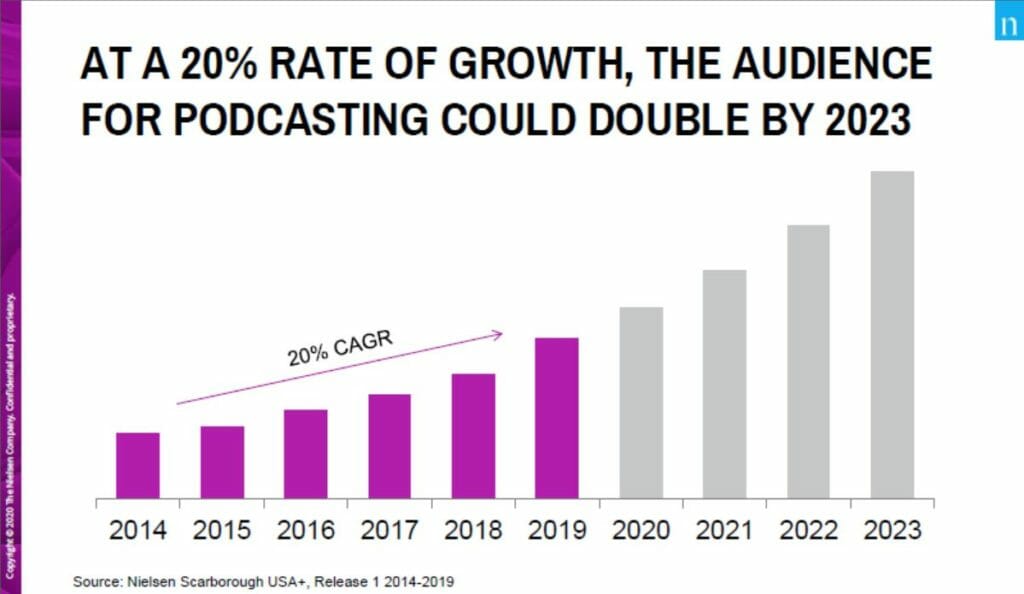

[01:16:42] Tilman Versch: Let’s move away from the music industry to the podcast market. As you can see, I brought some graphics here. You can see the growth of the podcast audience. It’s estimated to grow 20% CAGR over the next few years. They guess that it will double by 2023.

The next graphic is the unique podcast account by year. We already mentioned this. There are so many new podcasts on Spotify that are growing, and the podcast producer market is widening. We see the podcast market growing strongly, but I think also from my experience as a creator myself, there are still many hurdles in the creation and growth aspects of podcasts. What do you think should be done on the producer side or what innovations will unlock even more growth? What helps or has helped some producers to produce podcasts?

[01:17:46] Sleepwell Capital: I think when it comes to the hurdlsoures that I think Spotify is focusing on solving the next couple of years and should be a very big enabler for the marketing in general, one is discoverability because podcasts still suffer from not finding the right audience. You just need to promote it on social media and things like that. You don’t have the same tools as you would if you were a musician and just aiming to get on a certain playlist and having the algorithm recommend you a song based off what you listen to. I think that’s the next frontier when it comes to podcasting on one side.

The other part is monetization because the better and the easier that it gets to monetize your podcast as a creator, it’s going to be, not only better for the creators but it’s going to bring in more and more creators and almost a more professional high budget produced content. So, it’s going to be better for everyone in my opinion. This is both advertising, subscriptions. It’s all being tested out as we speak because it’s such a new market. I don’t know what you want to add to that Jeremy.

[01:19:25] Jeremy Deal: I don’t think we understand just how far behind audio is, or talk audio is, podcasting is. I mean, there are some really interesting statistics out there. But just to zoom out a minute and think about how hard it would be.

So, this interviews we’re doing. Let’s say it’s an hour and a half or two hours in total. Yeah, I could post it on Instagram but what percentage of people are going to listen to it? If they did click on it, how many people would actually listen to the full episode. I guess if you were really into this and you were doing research on Spotify you would, but it’s more likely that the people that listen to it will come at it from a different way.

So, the tools that allow social media to grow exponentially just don’t really apply to audio in general, but especially to podcasts. This is because podcasts are so specific. They’re so long. They’re so specific to what you’re interested in and there’s just so many podcasts coming out every day. I had a couple of notes from an interesting Doug Embrace interview from the Founder of Pods which was recently acquired by Spotify on the Not Boring Podcast, which I recommend. One of the stats they talked about was that the average podcast or the median podcast has downloaded only 123 times and I guarantee that will go down as the number of podcasts go up or are put out into the system. Finding a way to bring audio into the modern era of discoverability and search ability is really the real opportunity for Spotify. It’s not just in talk, but also in music as well.

On the podcast side, as Gustav Soderstrom, the Chief Technology Officer of Spotify has talked about, it’s easier for them to experiment with these tools in podcasting because they have complete control over that versus the labels that are harder to work with and slower to move because they don’t want to disintermediate their own cash flows. The opportunity to socialize or to make podcasts discoverable and people to actually listen to them is a really interesting challenge.

The opportunity to socialize or to make podcasts discoverable and people to actually listen to them is a really interesting challenge.

Jeremy Deal

The Pods acquisition is an example of, I think, where that industry is going and what the opportunity really is there, because social media is designed for pictures, posts, and blogs. Look at what people post on Facebook, Instagram, or twitter. It’s just different. Audio is inherently difficult socially. Daniel Ek talks about this. There are other people as well, but I think the path they’re going down to fix this or to unlock this opportunity is what Pods is doing. That interview with Doug and Bruce is really fascinating. I think there’s a variety of ways they’re going about it.

Pods itself, and I’ve played around with it just a little, builds a social profile that is very similar to what Spotify does on the music side. It uses machine learning to pull out snip bits, little pieces, maybe one or two sentences that are really the heart of a podcast or something interesting. And then, it builds a cohort of those, collects, and puts those together. So, when somebody searches a topic on Pods, and the example in the interview they gave was COVID-19, it could potentially produce one or two lines of talk from five or six podcasts from really credible people that have given in the last six months. It’s a way for those creators to be heard and it creates a short-form version of something that was really long and tedious and difficult.

Pods itself, and I’ve played around with it just a little, builds a social profile that is very similar to what Spotify does on the music side. It uses machine learning to pull out snip bits, little pieces, maybe one or two sentences that are really the heart of a podcast or something interesting. And then, it builds a cohort of those, collects, and puts those together.

Jeremy Deal

For example, when I do stock research, I rely on podcasting quite a bit. Sometimes, there’ll be a keyword in a specific stock or company I’m researching, and I know that there’s a podcast. I listen to the podcast for an hour. I don’t want to listen to the whole thing, so I keep hitting the forward button. I just want to hear what this random person has to say about this stock and maybe the podcast is on something totally different. So, if I could pull out that one key piece that I’m interested in and have that packaged with similar data that is given to me just like a google search, it’s a way for creators to be discovered. I think they are paths forward today but think there’s going to be more tools like this, especially with live audio.

RSS technology

[01:25:11] Tilman Versch: RSS is still a big thing in podcasts. Why is that bad?

[01:25:16] Sleepwell Capital: RSS, I think, was basically designed in the 90s. It’s a directory. It pushes, whether it’s an email. Or in the case of a podcast, it’s just an mp3 and you just automatically download that. Besides that, you have no real traceability or engagement metrics that tell you whether the person is going to listen to the podcast or not. Forget about monetization as well because the only supported advertising format would be the creator just reading out whatever brand they’re partnering with. Again, you can’t really measure if that listener listened to that part or not.

When Spotify decided to get into podcasting, it was a little bit controversial in the beginning because they obviously embraced their streaming nature which they were built on top of. They’re very true to that, right? In large part, because you would be able to get these metrics and now more recently, we’ve seen that you have the capabilities of dynamically inserting advertising that can be targeted to the specific listener.

In the beginning, the reason they were criticized a lot was that in many ways it was considered like a closed-end ecosystem for podcasting, but I think more recently that they have announced this more open-ended platform through the use of Anchor which is the podcasting hosting company that Spotify bought. They’ve actually proven that they’re going to be much more creator-friendly than otherwise, some people would have thought.

I’ve been reading Ben Thompson for a couple of years now. Originally, he was a big critic of Spotify’s stance on podcasting to the extent that he ended up pulling all his podcasts from the platform, but once Spotify came back and announced their intention to be a more creator-friendly and open-ended audience network and not really taking a lot from creators, especially compared to Apple, he basically completely did a complete 180 and brought all his podcasts back to Spotify and recognized that they were doing the right thing. I thought that was super interesting.

Spotify’s open access model

[01:28:14] Jeremy Deal: I could just add to that that the typical Walled Garden model that social media uses is in the opposite direction that Spotify is going now. The Walled Garden model is you post your content on Facebook, you don’t get anything for it and Facebook just makes money from it. It’s a one-way monetization. Spotify looked up and said, “Okay. We want to create this platform that’s different from RSS.” The way I understand it is RSS wasn’t possible in streaming. I don’t understand the technical reason for it. Or maybe it wasn’t possible for them, or all of the streaming. I’m not sure.

The Walled Garden model is you post your content on Facebook, you don’t get anything for it and Facebook just makes money from it. It’s a one-way monetization. Spotify looked up and said, “Okay. We want to create this platform that’s different from RSS.” The way I understand it is RSS wasn’t possible in streaming.

This open-access platform allows podcasts owners, the example that was recently talked about in a podcast with Gustav on the Means of Creation podcast, if listeners haven’t listened to that, was it allows even the large content owners like the New York Times or something like that to post their content on Spotify and decide if they want to use their billing platform or not. If they already have a subscriber base like Ben Thompson and they already have a billing base, it allows them to put that on there and be able to have complete control over that.

With Apple podcasts, you do not have access to your user base. So, if you’re trying to build a subscriber base, you can’t get their emails for example. You can’t interact with your users directly. You have to use their billing system. If you have an existing podcast with a million followers or a million paid subscribers, you can’t move it to Apple. And before, you couldn’t move it to Spotify either. I think that was Ben Thompson’s problem with it because in order to move it, you would have to ask all of your subscribers to unsubscribe and re-subscribe all over again to Anchor.

So, now in the open-access platform protocol, it allows you to move your material over to Spotify. If you don’t want to use their billing system, you don’t have to. You can continue using it. It also allows you to decide if you want to monetize and add insertion streaming technology or not. You can use your own.

What Spotify gets out of this is the access to the data. They want everybody. They want all audio available on Spotify which makes perfect sense. As Gustav, the Chief Technology Officer says, there’s no way we can have all audio on the platform if we have to monetize all the audio. Inherently, a lot of people say, “No, we don’t want Spotify to monetize it. We want full control. We want to monetize it.” That’s why Apple doesn’t have access to a lot of the audio because Apple highly controls the way it’s monetized and it doesn’t allow you to have interaction with the subscribers.

They want all audio available on Spotify which makes perfect sense. As Gustav, the Chief Technology Officer says, there’s no way we can have all audio on the platform if we have to monetize all the audio.

Jeremy Deal

So, this is Spotify going in the complete opposite direction saying, “We don’t want to be a Walled Garden. We want to build products that are inviting that make the podcast owner want to be on Spotify.” And then, choose if they want to monetize with Spotify or not. Either way, we want to make sure they’re on the platform. And so, it basically gives you zero excuse to not be on Spotify. Even a competing podcast company would have no choice. There’s no downside to allowing Spotify to distribute your product. I mean, they’re in 178 countries. You can upload it on Spotify.

You could continue monetizing yourself and have nothing to do with Spotify. Spotify also wins because the person in whatever country can access it as everything is available on one player. Actually, ultimately, Spotify is really winning slowly in the background. Even when the creator is choosing not to monetize on Spotify. So, the open-access platform is a really big deal because it creates a no excuse situation for everybody, including the large podcasts and competitors. It allows Spotify to be one of however many distributors.