The CEO of VNV Global, Per Brilioth, was interviewed in March 2021. Here you can find the transcript of our full interview as well as the podcast.

- Per Brilioth's biggest mistakes during his time at VNV Global

- Portfolio evolution

- Divest from oil assets

- Relearning and unlearning

- Going global

- Building a global network for VNV

- The change in the shareholder base

- Investing as a listed company in private companies

- Being an active shareholder

- Insider ownership

- Giving capital back to shareholders

- Selling listed assets

- Generating ideas

- Per's assignments in other companies and his publicly visible investments

- Idea selection at VNV Global

- Importance of management

- Character traits of “bad” management

- The role of optionalities

- Risk and reward

- Per Brilioth on the current portfolio

- A metaphor for the portfolio

- VNV Global's next-gen stars

- Strong founders

- The role of data

- Established players in the portfolio

- Babylon Health

- What makes Babylon the leader?

- Babylon in 3-5 years

- Will VNV Global still be a shareholder in Babylon in 3-5 Years?

- New areas of investment for VNV Global

- Climate and network effects

- VNV Global in 5 years

- Growth in VNV Global's team

- Long-term investing

- Disclaimer

Per Brilioth’s biggest mistakes during his time at VNV Global

[00:00:00] Tilman Versch: Hello Per. It’s great to have you on for our Good Investing Talks. How are you doing?

[00:00:07] Per Brilioth: I’m fine thank you. How are you?

[00:00:09] Tilman Versch: I’m good. I’m happy to have you here and have the chance to talk with you about the Vostok Nafta, Vostok ventures, and VNV global and to get to know the company a bit better. You’ve been 20 years in the company, I think, or already 21. Is this true?

[00:00:29] Per Brilioth: Yeah. Yeah. It’s of that order. I joined in September 2000.

[00:00:35] Tilman Versch: Then let me start with a bit of a challenging question for the beginning. What were your biggest mistakes and the times you’ve been at Vostok? But before you answer, I want to use the time to just show the disclaimer and show some information and you have some time to think about it.

You already know the methods from the disclaimer I’m giving you. All we are doing here is a qualified talk. It’s not advice and recommendation and always do your own work. And at this point, I also have to disclose that I’m holding a position at VNV global, so, I might be a bit biased. Take all of my interviews and this talk from me as me being a shareholder. Then coming back to your Per, what is your answer to my big challenging question?

[00:01:32] Per Brilioth: No, there are too many answers I think. Throughout all these years, we’ve been exposed to volatile markets. And especially as we were very focused on Eastern Europe and especially Russia for many years, so it’s been a volatile market and you become absolutely mad if you start to trade with a rearview mirror, but if you allow yourself that and you look at your mistakes and then, of course, there are certain points of time where you should have not stayed, you should have exited. Russia has gone to zero twice at least during my presence there. So, to see when things are getting out of hand, but at that period, we were also involved in the public markets in Russia. And we are very, very long-term investors. And the good thing about doing what we do now is that you have to be prepared for volatility, but we’re not traders.

We are long-term investors. So, that’s one thing that springs to mind, to sort of be mindful of macro volatility, and another one, I think is that we diluted ourselves many times too early in what we do today and that we let other shareholders in at a too low valuation. I think that’s especially relevant for Avito which was our large holding the Craigslist, if you will, of Russia. and when that company eventually was sold or we exited, we owned 13 and a half percent but we had the opportunity to own much more than that. We diluted ourselves along the way, which was a bad investment but it became very good in the end. The IRR was very good but it could have been better.

Portfolio evolution

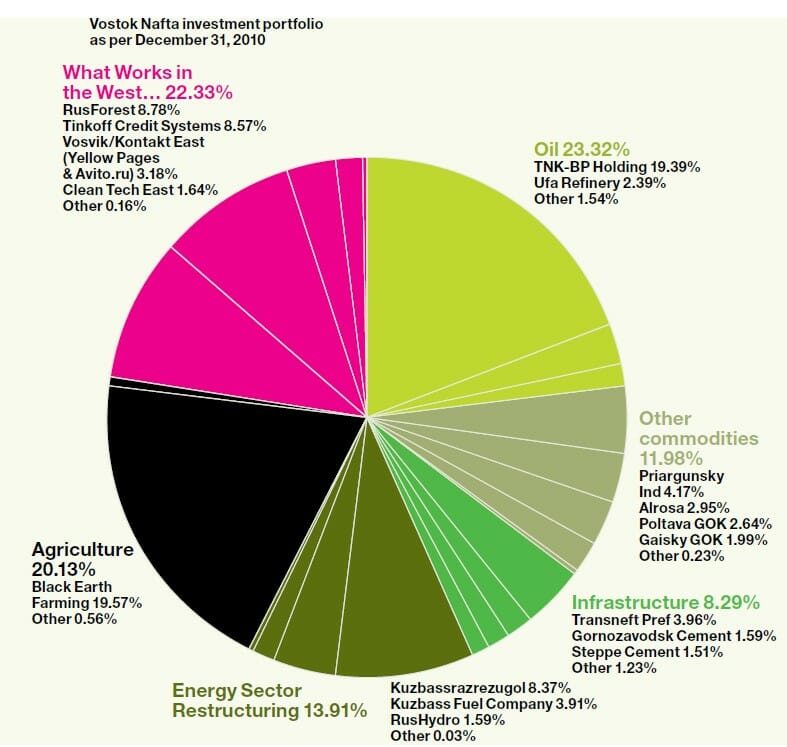

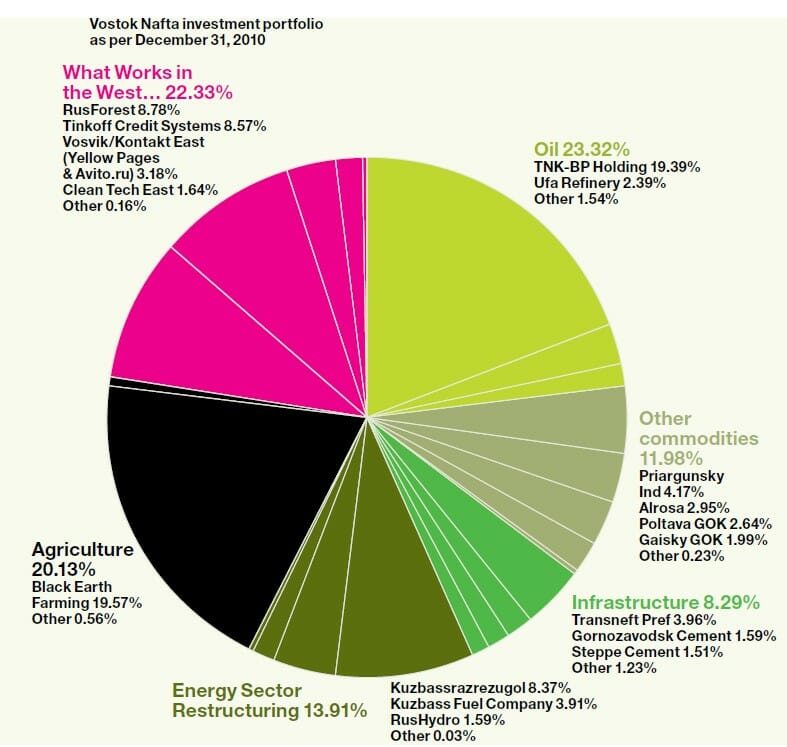

[00:03:43] Tilman Versch: Let’s take the chance for the beginning of the interview to look a bit back in your history. And I want to do this with free snippets from your annual reports. I’ve taken the portfolio from 2010, 2015, and 2020. I will share them with you in a second. Here, you have the portfolio from 2010 and I hope you already see it.

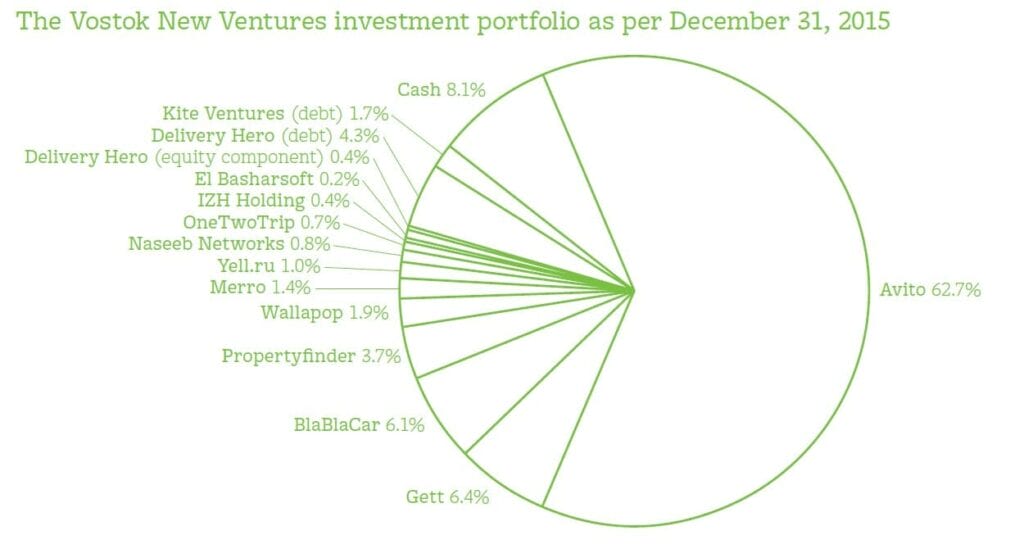

It is the early science that you’re turning into a tech investor in this portfolio. I will also show the portfolio of 2015. There, Avito is one of the biggest holdings, but you also had some of the tech investments and the portfolio of 2020 is here.

They have, you don’t have a pie anymore. So it’s a different way of presenting it, but maybe let’s go back a bit into the portfolio of 2010 and help me understand where you were coming from at this time as Vostok Nafta, and how also this kind of pink part of the portfolio became your biggest part of the portfolio. Why did you, let me say it like this, fall in love with this tech and Avito investments or Avito-based tech investments, maybe let’s try it like this?

[00:05:10] Per Brilioth: Yeah. Yeah, I know. I said where we came from, of course, that this company was founded by a Swedish oil and mining entrepreneur called Adolf Lundin. And he sort of, he had become, liquid for the first time in his life, in the early nineties. And that coincided with Russia becoming Russia again and not the Soviet Union and especially relevant for capital markets. And he grew very fascinated, but that you could sort of buy the assets that he was drilling after in a very expensive way. You could buy those very cheaply on the Russian stock exchange. He used the liquidity that he received from an exit he had done in Argentina to buy large parts of what was shares, in the newly privatized industry from the Soviet Union into the very young Russian capital markets. And then he formed Vostok around that and Vostok was very focused on his type of sector. And then what you see there in 2010, was it right there? We have a lot of large remnants. I think the largest order was TNK holding, which is an oil company. And there were the large mining assets also present there within different commodities.

And so the bulk of the portfolio was still sort of very heavily exposed to the traditional sectors of where we came from. But the pink part is I guess me starting to apply what has always been very important for us all the way from the mid-nineties to today is to have the portfolio that our typical shareholders cannot get exposed to themselves. Russia, in the nineties it was very difficult to buy Russian stocks. It took two or three months to settle. There were no ATRs. And so, we were like T plus three exposure to Russia, and with time sort of Russia became a more normal market and anyone could sort of trade it and anyone could analyze it. And then we started successfully sort of exiting, the parts of the markets which were easy for anyone to access and that led us to start to look at private opportunities. I guess around about 2005, we started doing private investments and there was a general skepticism around Russia. Can Russia ever become a normal country and a normal market?

The Russian consumers; do they really want to consume the things that we do in the Western. And we applied that to this concept of what works in the West, also works here in Russia. And so, we invested into business models that started to emerge in Russia that we saw were already very well spread and very loved by consumers in Western Europe and the US et cetera. And so that was the starting point, for that pink part of the portfolio. And there were different sort of aspects of that, but the one, the two that sort of grew and became, sort of very important for us was, think of credit systems, which started as a, a credit card issuer, a consumer finance bank with a credit card as its` main product, which over time has developed into Russia’s absolute leader in terms of FinTech bank. And the other one was Avito which was, which is the dominant online classified player in Russia.

Divest from oil assets

[00:09:12] Tilman Versch: When did it click for you, that this is the way to go on these investments, to divest from the oil assets?

[00:09:23] Per Brilioth: Well, I guess it started around the time of that annual report being issued, those non-tech investments are really, sort of, that was the frontier part of the Russian sort of listed capital markets. The final decision was taken in 2012 where we sold the entire portfolio and gave that money back to shareholders in the autumn of 2012. From then, we became a pure investor into private companies, but of course, then we still had a handful of private companies, which were exposed to not tech sectors, forestry, and farming, and those eventually became listed and we distributed those listed assets to our shareholders and became a newer, more pure tech around about that time.

Then in 2013, ‘14, we decided to focus our efforts on the Avito type of investments, the classified part, which we define as, you could describe them as businesses with the potential of very strong network effects and we can come back to that, but then we had, of course, a holding in this FinTech play. That FinTech play, listed in London in an IPO in November 2013. We sold most of the shares that we had into that IPO, but we still retained some shares. If you remember, 2014 was a very volatile year, certainly, for Russia, oil price tanked, which was negative. Then also Russia had this all Ukraine mess happen-start, with crime et cetera.

The listed Russian assets went down a lot and we didn’t think it was good for our shareholders to sell the rest of this FinTech bank, into the list, the market because the price had fallen a lot. At the same time, we also had investment opportunities around the FinTech space that we thought were interesting.

What that led to was that we spun off the FinTech portfolio and the opportunities into separate Vostok that was originally called Vostok emerging finance. And that happened in 2015. From 2015 and onwards, we were a pure network effects company in what we’ll just now call VME global.

Relearning and unlearning

[00:12:09] Tilman Versch: What did it mean for you to relearn and unlearn certain things in investing? Because investing in oil, forest assets and infrastructure assets is different from network effect platforms and the internet.

[00:12:25] Per Brilioth: I think the common denominator is, the ability to think and expose yourself to risk, right and that it’s okay to take risks. I’ve been brought up and this is the culture of these companies and the ability to take the risk, but only take the risk if you have the reward to compensate. I think we live and die by thinking about risk-reward and that’s very similar, regardless of which assets you invest into.

Of course, visibility into Russia becoming a normal consumer place, I guess, was lower in the mid-2000s than it is now. Now it’s, there is full visibility into it. and so you could say that we applied our risk appetite into that. In that sense, it was natural.

On the tech side, I was a small shareholder in the Swedish version of eBay from the early 2000s, I think like 2003, probably. I was on the board of that company, it’s called Traviela, and then in 2006 eBay bought Traviela and moved in their own management and the old management, they were free to go and do business only in countries where eBay wasn’t present and such a country was Russia.

I convinced the guys to move to Russia to apply their knowledge from the tech world into sort of what was happening in Russia. I bought the Russian business that was like an offline going into online business in yellow pages and they started there. But as with good management, they quickly understood that this wasn’t going anywhere and they looked at an eBay model but then they eventually settled for a classified model, and out of that came Avito.

Going global

[00:14:27] Tilman Versch: That’s quite interesting, this move. If we take a look back at your portfolio and look at 2015, you already see what is now part of your name, the global footprint within 2015, you still had a strong Russian footprint, but more sprinkles were coming on for global companies like BlaBlaCar or Gett, how did you develop this global way of investing and what helped you to become a global investor then instead of a niche investor for Russia?

[00:15:03] Per Brilioth: When we took the decision and this is, I guess, around 2013, ‘14, and eventually culminated in 2015, when we spun off the FinTech portfolio, in 2012, we sold everything that was listed. Get that money back to shareholders and we took the decision in 2013, 14, we should only do Avito type of investments. And then eventually we spun off the FinTech portfolio. But around that time, we also understood that that’s a good decision. We’ll apply what we’ve learned from having been part of Avito from the very first day, to new opportunities. But Avito was so dominant in Russia, so there’s nothing else to do in Russia. At that point in time, it became natural to open up the geographical sort of focus to elsewhere. And so we applied that initially, we applied that to other emerging markets, feeling that developed markets we were not ready for, but emerging markets, since we’ve been around Russia for such a long time, we felt, we knew, and I think we knew what’s important when you invest into those markets. We started looking at other emerging markets in our time zone, and that led us to a few investments in the Middle East.

Which is sort of similar to Russia as often misunderstood. We only think of it as desert oil and the violence, but in fact, there’s a large middle class there that’s growing too. I’d been brought up in the Middle East as a kid, so I felt comfortable in that part of the world. We started looking there but with time, we found that there were also opportunities which fitted sort of what we do in more developed markets and our first investments. I guess our first investments into more developed markets; one was a Delivery Hero, which is essentially Germany and BlaBlaCar of France where we saw very similar dynamics to Avito, very clear network effects.

We also saw that they had not been fully-sort of perhaps understood by markets and hence got involved in those two and with those two, we felt more and more comfortable. We got more and more deal flow from all over the world and we capitalized on some of that deal flow.

The opportunities came elsewhere, then Russia, we still look at Russia. We still do deals in Russia, but it’s just that the larger set of opportunities have come from elsewhere.

Building a global network for VNV

[00:17:54] Tilman Versch: Investing is partly also about networking. And how did you go about building your global network for VNV?

[00:18:05] Per Brilioth: I think Avito there has helped a lot, as well as Avito, became such a large company and one of the leaders in the global sense in the online classified industry and us being part of that since day one and me being part of Traviela earlier than that, and of course, the team of Avito being part of Traviela.

I think in the mid-2000s, online classifieds, wasn’t really an industry that anyone invested into. Right. It was Craigslist, it was private ships that were still newspapers, Naspers was doing other stuff. We were early in that space and as the Avito grew, the sector sort of grew in general as well. Then we became well known for being around. We became well-known with sort of Avito becoming the kind of company it is today. I mean a large, very well-run company.

The change in the shareholder base

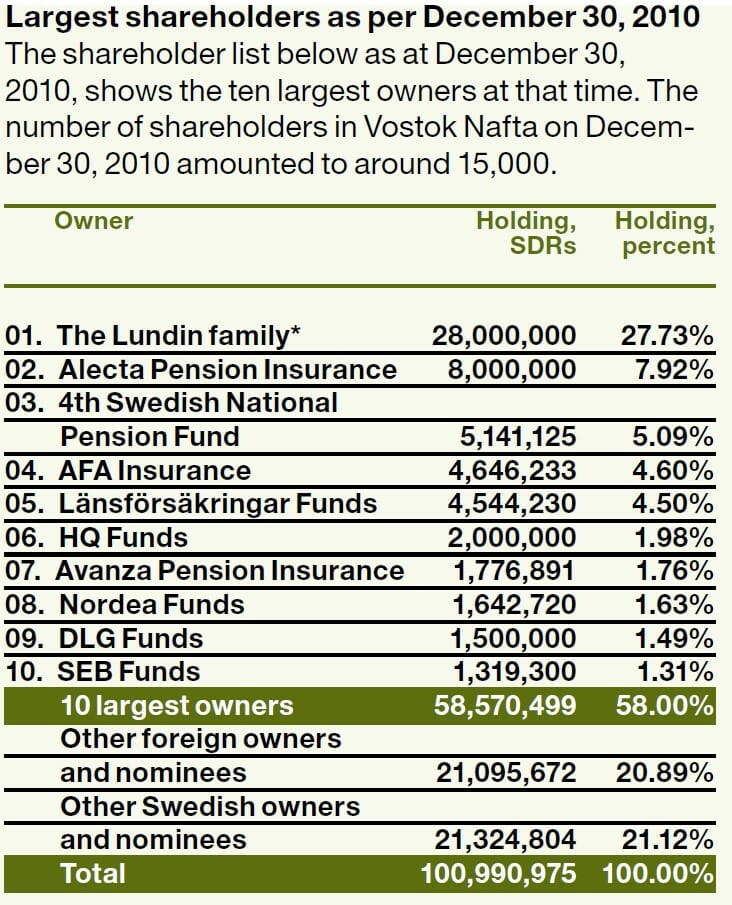

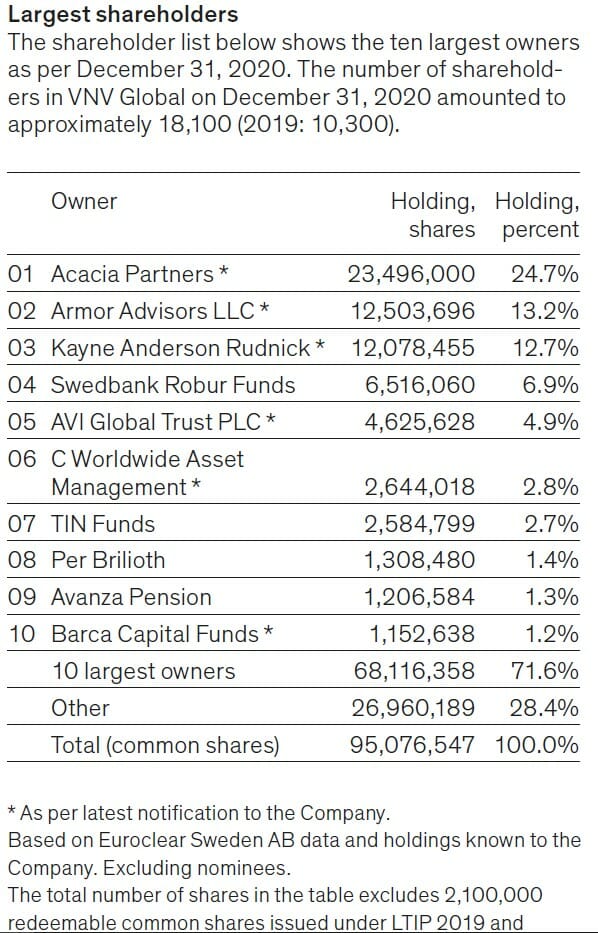

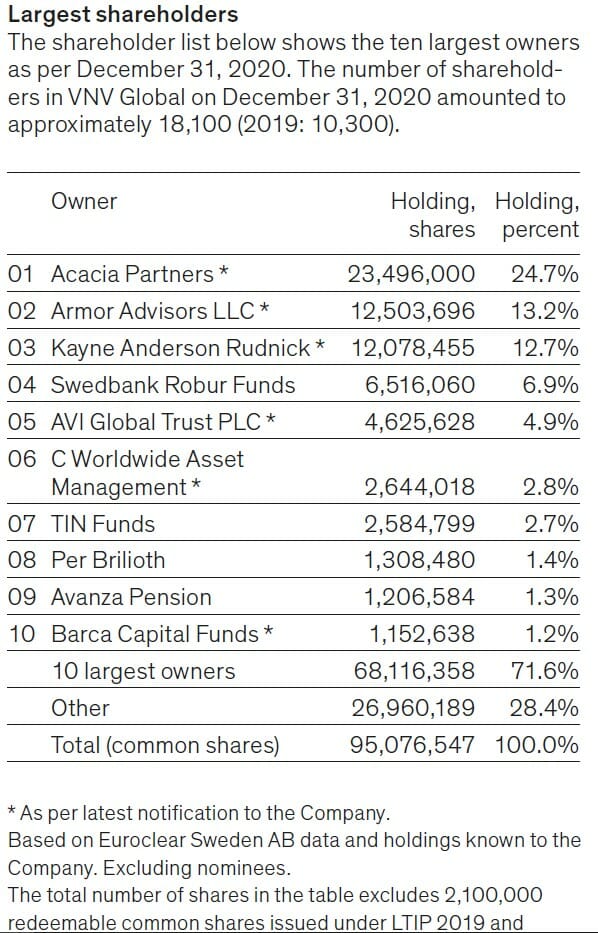

[00:19:21] Tilman Versch: As you went on this journey, you always, as a listed company, you always have like, I think around 10,000 people standing behind you or institutions and people, your shareholders, and it’s also quite interesting. I want to show you the next chart that I also did get from your annual reports. Sorry, here we go. And it’s the list of your shareholders that also changed, since 2010 a bit.

Here you see 2015.

Here is 2020.

My question is, what I found quite interesting in your list of shareholders if you look at the 10 largest shareholders, you always had a high concentration of shareholders over like 58 or 70%, how does this help you to run the company?

[00:20:24] Per Brilioth: I think we run the company regardless, sort of all the concentration of shareholders. For many years, our largest shareholders were also the same family that started the company. So, they populated the board as family members, they were very involved in the decision-making. So, it’s always been very natural for us to have one large shareholder. They eventually sold their shares to a US outfit called Luxor capital, which was very focused and very attracted to online classified ships and those types of industries. They still are. They were also, they’re not obviously in a family, but they’re also quite active, not directly because they didn’t sit on the board directly, but they were very sort of close and were very interested. I’d still say that our largest shareholders today are all very sort of responsive and very supportive, and they share that with the kind of ownership that we’ve had in the past. But they’re perhaps not as sort of directly involved as the initial family, so that’s digressed over time. I think it’s natural when the founding families are involved, they stay quiet sort of involved directly.

But as that moves over to more institutional capital be it sort of, large percentages, it becomes more passive even though they’re very, very responsive and supportive.

Investing as a listed company in private companies

[00:22:18] Tilman Versch: You use the term active shareholders for yourself, maybe before we go into a definition, I want to go a step back. If you think about them and I already talked to your analysts about this.

That you’re a listed company, but you’re investing in private companies. So, there’s always a tension in between the information you want to share with your shareholders, that they are confident that you’re doing the right decisions and the information the companies you’re investing in want to disclose. How are you going about this? How are you managing this constant struggle?

[00:22:57] Per Brilioth: The unwillingness to share information from phone companies typically is most relevant or most strong in the very early days when, especially in the space where we are investing where with network effects, we say that it takes about five years before you’ve built enough liquidity in the marketplace or enough data, in other situations to be able to, charge for your products at all. In those early years, it becomes very important to not share too much information because there’s still competition once you’ve moved out of that phase, the whole idea of very high barriers of entry being built and, makes it assume characteristics of winner takes everything. Once you’ve sort of achieved that, then there is no competition, right? Then it becomes more, they are able to more or less sort of rate share information like Avito went from sharing nothing to sharing revenue and margins and quite a bit of things.

We are mindful of that with our companies, and whilst they are not in a position to share information at all, we help our shareholders, and try to explain how we think about this investment, and to use KPIs and metrics and data that are widely available, perhaps from daily visitors or number of visits or done number of downloads, et cetera.

So, you can track sort of that something is happening in the right direction. Then, when the company starts to approach, kind of a dominant position, we prepare them and to hold the hand of them, to be able to successively, start to share some information.

As you see in our portfolio today, Babylon and BlaBlaCar have gotten to the stage where we don’t share the same kind of information that we did for Avito in the end, but they let us share some information. With that information, you can build like a crude, even if it’s crude, but you can still build some kind of starting point as a financial analyst, of how the company is doing.

Being an active shareholder

[00:25:45] Tilman Versch: How are you defining the active shareholder or inactive shareholders?

[00:25:51] Per Brilioth: Active stems from the early 2000s where we were very active in the Russian capital, an inactive shareholder in Russian capital the markets wherein these early phases of emerging markets, development, corporate governance is not understood. In the early days, we were very active about getting involved in situations, which were very undervalued because of corporate governance risk. We were active in dismantling the risks of corporate governance. So, the activeness stems from those States when it’s more of a tradition in the, even in the Western sort of space that you, where inactive shareholders, become a large shareholder and then, helps the management and other shareholders to understand the why it’s important to think about being a good corporate citizen, good corporate governance. But that has relevance to what we do today, not because any of these companies are all running sort of a hundred percent good in town to corporate governance, et cetera, but we are active in other ways. So, we’re on the board of our companies, I guess that’s the most relevant check for being an active shareholder.

If the board is difficult to be active, then I think we don’t define active as running the companies. We try to be very clear to both our shareholders and also our portfolio companies that we are not going to run these companies. That’s a bad idea. I mean, we’ve never run companies, we spent a lot of time on investing. When we do the due diligence of our investment work, we spend a lot of time on understanding that the founders don’t need that help from the shareholders. So, active, doesn’t mean that we run the companies, but active is that we are board members and we’re very supportive board members for these companies as they go through the early innings of their life.

I think that’s where we play a role in terms of activism. I think if you ask our difference among entrepreneurs and founders, I think they felt that it was good to have us around because it’s a difficult journey. It’s a volatile journey and it doesn’t, it never goes how you think it’s going to go. Never. So, to have someone there who’s is going to be there as long as you are there, and that will always be supportive and someone to talk to, the guys are not someone who’s looking to make decisions to sell the company tomorrow. They’re going to be here for the long-term. I think that’s the comfort and I think we define activism in that way today.

Insider ownership

[00:28:56] Tilman Versch: How has the concept of ownership changed? Because if I look at the shareholder’s list, you’re appearing there under the top 10 shareholders in my free snippets, for the first time in 2020, that there’s something changed in the concept of ownership. Are you saying your members should, or your team members should get more ownership over the years?

[00:29:25] Per Brilioth: You mean, the way we think about ownership in our portfolio companies?

[00:29:28] Tilman Versch: No. How do you think about ownership of the people working at VNV and owning shares of VNV, and having shares of the compensation and the share orientation?

[00:29:39] Per Brilioth: Yeah, that’s always been the case, right? I mean, it’s always been the case throughout the life of this company that the people who work there have been predominantly incentivized by being exposed to the share. In the initial, in the first sort of decades, we had simple stock options, now we have more. It’s essentially stock options, but it’s structured in a way that’s more standard here in Sweden. It’s very equity-linked. So, over time, the shareholding of the people who work here who have all worked there quite a while, I mean, I’ve worked here the longest, but all the others have worked here for quite a few years and it’s successfully been, become larger and larger shareholders.

Giving capital back to shareholders

[00:30:33] Tilman Versch: How do you think about giving capital back to shareholders? You did two interesting moves I think, the spinoff of Vostok emerging finance was one and then one or two years ago, you gave back a certain portion of the capital you did get from the Avito sale.

How you’re thinking about this and how you’re going about this?

[00:30:54] Per Brilioth: Ever since I’ve been at this company, we’ve been very disciplined with not sitting on liquidity if we don’t have anything to do with that liquidity. We have throughout the years, been a buyer of our stock in the market as we traded at a discount to nav, we’ve always been a buyer and in that way, essentially distributed cash to shareholders. Since we are incentivized by the stock, we’re not incentivized to have this company large just to have it large. It’s not a fund, we don’t have a management fee, we don’t take a percentage of large petroleum. So, we’re not incentivized for that. We’re incentivized for these shares to go up in value and if it makes sense to make it smaller for the one share to go up in value, then, we’ll do that. I think that’s very fresh I think is very important and it’s led to us distributing cash when we’ve had too much cash or distributing assets when there was no need for our shareholders to get exposed to, that`s an asset to us. I think that’s also led us to believe that if we, then, in a different scenario have deals, investments that we think are in the interest of our shareholders do get exposed to, then we can go back and ask for this money.

But then we of course have to explain that we’re gonna have to invest it into this company. This looks like this, it fits our strategy. I think that’s worked well.

Selling listed assets

[00:32:38] Tilman Versch: How is the orientation about selling, also about your shareholders? I think you have this law, if something is listed, you sell it, and if the founders sell their stake you sell it as well because shareholders can try to buy this themselves or what is the take on this?

[00:32:56] Per Brilioth: It’s not quite a law, right? It’s not written into our company charter that if something is listed down there, we immediately have to sell it. We can hold listed assets but we’re never going to buy a listed asset because you, as a shareholder or big pension fund, they can do that themselves they don’t need us to do that or the cost layer of loss.

But if we have something that’s in our portfolio that we’ve lived with a private company that eventually lists if it doesn’t make sense for us to sell it either because there’s still upside or for other reasons, then we can still sit on it for a while, but I don’t think you should see us long-term sitting on assets that are listed and then we either sell them or we distribute them to our shareholders.

Generating ideas

[00:33:51] Tilman Versch: That’s an interesting way of going about listed assets. But before you have something, the chance to have something listed, you have to find ideas. How are you going about generating or getting ideas and VNV?

[00:34:10] Per Brilioth: Well, one thing is fixed in this volatile world, right? That is what we look for when we invest. We look for network effects and we define that as the company, the product that the company sells becomes more attractive with one every new user. With one more new user, the product becomes a little bit better.

That, in turn, attracts another user or makes the product a little bit better. So, you’re off in that spin, that’s number one. Number two is that the markets that they are disrupting or active in have to be large. Number three is that the founder has to be very strong and very able to navigate, things that will happen that we won’t foresee right now.

So, that’s fixed, but then you can apply this. We started in classifieds, which is maybe the Holy grail of these network effects. It’s a winner, takes everything type of market. But then we found this in other situations, we found it in BlaBlaCar, Delivery Hero. Those things are perfect for, they have the same characteristics.

We’ve recently also found that in terms of, the one who has the most data wins. In those spaces, I think we’ve become quite well-known in the concept of network effects. We get deal flow ideas. What to do from founders should come to us because they’ve seen us, as owners in other companies, VCs, we don’t compete with VCs.

We don’t raise money from the same people. We typically stay longer than VCs. So, they don’t see us as competitors. We have a relationship where we invest alongside them, and then sometimes we seek out situations ourselves as well. So, the ideas come from a variety of different sources.

Per’s assignments in other companies and his publicly visible investments

[00:36:20] Tilman Versch: You are having assignments and a few other companies that are shown if you’re going on, some portals that show them, like, for instance, The Org.com, how helpful are the assignments? I mean, this list, I’m not sure if they are, if this is the correct list, but…

[00:36:39] Per Brilioth: Oh yeah. Okay. That okay. I see what you mean.

Yeah, no, exactly. There’s some, I mean, most of these things are very, very small private situations. I, I do invest some privately outside of our stock. Nothing that sort of competes with our stock. That’s the law but I’m very interested in music. I have some investments in music. That’s the main thing.

[00:37:09] Tilman Versch: Are these investments helpful for the work at VNV or are they separate spheres?

[00:37:16] Per Brilioth: Some of them are helpful in terms of expanding the network. I think in that sense they’re helpful. But, otherwise, a company is a company, as you can see that there are some benefits. You always learn when you’re involved in different companies and they have troubles or they have wins, but it’s indirect like that; the benefits.

[00:37:48] Tilman Versch: If you invest in music, just one question, what’s your favorite music? Or do you have no favorite music?

[00:37:55] Per Brilioth: You mean in terms of the type of music or type of investment into music?

[00:37:57] Tilman Versch: What type of music do you like most here?

[00:38:01] Per Brilioth: Yeah, I’m born in 1969. So I think the music we listened to when we were in those very formative years of 13, 14, 15, 16, that sticks with you. I grew up looking at this Irish band, U2 playing in Germany. I saw it on Swedish television and I got fascinated by that. I think if you asked me, U2 and Springsteen, I think I’ve seen those two groups 40 times over the years, 40 concerts. Those would be the main ones.

Idea selection at VNV Global

[00:38:42] Tilman Versch: Interesting. I also liked them but coming back to the ideas is also a bit like music selection that you want to have the good music you can stick to and sought them out because there’s so much on offer. So, what is your way to finding ideas, the needle in the haystack for VNV?

[00:39:02] Per Brilioth: On ideas for investments? I think you have to be curious about new things. You have to be positive and receptive to new ideas and if you are that then that attracts people who are interested in building new things. You get exposed to people that come to you who know that the door is always open.

They may not always invest, but they will pretty much always listen, and that gives you a lot of inflow of ideas and then to choose which one, you learn over time. Often these companies that we invest in are so young, so there’s not a lot of data to go through.

There’s not a lot of history and annual reports, et cetera. You have to form a view in using other sources, spending time with the people mainly looking at the markets.

Importance of management

[00:40:21] Tilman Versch: How important is the management in this process, the people, especially if the companies are smaller, I think that management plays a more important role compared to bigger companies?

[00:40:35] Per Brilioth: You’re a hundred percent, right. It’s everything. I mean, especially when you’re investing in these young companies and young companies active in spaces where they’re sort of destructing old industries, right? You don’t know like we are in health today. I think we all agree upon that the health sector will be more digitalized in five years and in 10 years, But, to understand exactly now how what kind of business models, how will, who will pay, what will be important? The visibility into that is very, very low. So, you have to have management, to be able to adapt, and maybe have to change the direction from there to there, in terms of, the focus of the company. Management is the most important, absolutely super important. I think where we have been very successful in terms of investments, the common denominator amongst those is that the management has been that, very strong, very strong sounds like they’re just strong in terms of muscular, but very intellectually, sort of creative and have a lot of persistency but also been able to adapt a lot. The ones will be successful, there’s been management that has characteristics like those and others where we have failed, it’s often been that we’ve been wrong about the management. That we didn’t have all these things that we thought they maybe had when we invested.

Character traits of “bad” management

[00:42:17] Tilman Versch: Are there some character traits over the years you found, I shouldn’t invest with people that are like this?

[00:42:26] Per Brilioth: That’s difficult to say. There’s no, I don’t think there’s one. There’s no ABC rule book on that you have to spend time, and people can be different, but still have habits.

[00:42:37] Tilman Versch: You mentioned the other sources you’re looking at to understand companies that don’t have the big history, but you’re interested in investing in what are examples for those other sources?

[00:42:49] Per Brilioth: Well as you said, our very first and foremost management and the people that they have sort of gathered around themselves. Then we try to get to know them by spending time with them but also spending time with people where they’ve been in the past understanding them, but other more quantitative sources are perhaps if they have a product that’s sort of been tested somewhat, you can look at how many downloads, traffic, conversion, there’s data that you can analyze, you mine that data and you get a better picture of how they’ve fared so far.

[00:43:48] Tilman Versch: Some of your investments, maybe if I’m thinking about Avito with these characters of the market, only the sky seems to be the limit. If you’re assessing a company and getting to know them, how much do you want to look into the future? What kind of picture are you forming about the future the company can have and are you thinking about optionalities in this way that are coming up?

[00:44:15] Per Brilioth: Yep. Sometimes it’s easy and like, this concept that you took us back to what works in the West will work in the East is that also for Avito, we looked at Chipset, and we saw how much revenue there was per every user in the Chipset markets. And we saw that, at Avito, it was, one hundred of that, and that was not relevant. It should go up but in many cases now, especially now in our portfolio, we are in companies that are maybe all global leaders in the space so that there is no one to benchmark against.

Then it becomes more difficult, to know how does it look at maturity? How does it look when you’re done kind of thing? So, then you have to form a view around that in other ways.

The role of optionalities

[00:45:13] Tilman Versch: What role do optionalities play for you? If you’re trying to value the company.

[00:45:24] Per Brilioth: Yeah, it’s all about optionality, right. Typically a startup is an option. So, beyond that, we typically don’t put a value on the optionality and see that as an upside, so that, I don’t know what’s a good example, but Avito was a company focused on Russia and was so strong in terms of tech and knowledge about running the space and building the space in emerging markets so that they, at some point of time also decided to apply that to other emerging markets.

That was obviously optionality on the upside. We never really valued that, but if it worked, then that would create value and the same is present I think in the companies we have today. Void, for example, is the European leader in e-scooters. They have applied for a license in New York.

That’s optionality on the upside. We don’t put that in the model we make when we decide on how to invest in Void. But if it works, it’s optionality on the upside.

Risk and reward

[00:46:35] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned that thinking about risk and reward is something that I can wake you up in the morning at three, and we can talk about risk and reward. If you’re happy to talk with me at this time. What kind of risk of a new reward are you looking for in a company and an investment?

[00:46:55] Per Brilioth: Yeah, well, I think, looking at network effects very high, very strangely, right? Like businesses, you’d want to own forever and then, apply that to very large markets like classifieds in Russia, for example, very large markets, 150 million people, largely, the potential is there. That’s our starting point. If this works well, this could go up a hundred times or 50 times, et cetera, then, okay. So, what risks do we have to expose ourselves to have to be exposed to that upside? And then, and then we look at that, we probably have to put in this much money, we could lose it all, and then we put, the same amount of money again, and then there, you see if the risk-reward stacks up. So I think that’s in a crude way, how we go about it.

Per Brilioth on the current portfolio

[00:47:57] Tilman Versch: Then maybe let’s go have a look again at the portfolio.

Maybe help us to understand, if you have smaller positions like drop net is at 0.1%, are these the small bets where you’re thinking they will double, are how you go about these positions in the portfolio?

[00:48:24] Per Brilioth: The small bets we’ll go many times. We typically start small, since we get involved, we can get involved early or we can get involved late also, but we can get involved early, and when you get involved early in this space where it takes, our rule of thumb is it takes five years before you have any revenue at all. The companies are subject to a lot of risks in these first five years, hopefully, slowly coming down the value coming up. But the point is that there, the value, in the beginning, is slow, the tickets are low.

So, we get, hence they don’t measure up much in the portfolio, but if they perform with hope and I think they will over these five years then, there’s enormous leverage of the upside on them and they will grow as a part of the portfolio. Avito started as a $4 million investment, they ended up being a $540 million investment.

[00:49:27] Tilman Versch: That’s more than doubling.

[00:49:29] Per Brilioth: That’s more than doubling yes, but when we started Avito we put that first money and, it was SharePoint 1% of the portfolio, if that, I remember the family-owned it, they said, para what’s, this is, they call it Paris kindergarten and the parent can play with these things.

It’s, there are no assets, it’s nothing. But anyway, but if you don’t do the small things, you miss the big thing, some of the small things grow. So, we have now a portfolio, what is it now four or five names that makeup about 70, 75% of the portfolio. Those four or five names, you would have mentioned that when, if you talked to me two years ago, two and a half years ago, when we had the large holding in Avito, they were in the shadows of Avito. In the same way today, we have companies that are in the shadows of Babylon and BlaBlaCar, and in time they will come out of that shadow. Small things grow.

A metaphor for the portfolio

[00:50:37] Tilman Versch: You mentioned the kindergarten picture about the portfolio. Is there any picture you’re using to, describe your way of approaching the portfolio? Sometimes it’s the soccer trainer who sets up the team and puts some on the offense or it might be the gardener who’s set, small plant links that become big trees, or how you’re going about the picture or the composition of the portfolio?

[00:51:09] Per Brilioth: The composition of the portfolio, we don’t think so much about. I try to be very clear to our shareholders also about that, that we’re not going to build a diversified portfolio for you. If Babylon were to list and were to double, it will be 50% of the portfolio. Fine. We’re not going to, and if we think it will go another five times from there, which we think it will not, we will keep it, and then we’re not going to sell it down so that, it’s exactly one-third of the portfolio. Or exactly 25% of the portfolio. We sort of, adhere to this old concept, I don’t know who said it. I know Barton Biggs or Morgan Stanley used it a lot. Maybe he meant it. That diversification kills the portfolios. You have to be able to understand the risks you have and not hide behind diversification.

Anyway, I know the mathematical sort of benefit of diversification, but we try to be clear about that so if we run a portfolio, that’s subject to a lot of risks and also, I think very impressive upside, but if you want to diversify a portfolio, you have to do that at the shareholder level.

That’s to the extent of the composition of the portfolio. Did you say something else as well? Remind me.

[00:52:34] Tilman Versch: Your picture, how you’re going about…

[00:52:38] Per Brilioth: Yeah, no, I recently wrote a piece about tennis. Apart from music, I’m a tennis fan. I don’t know if you see my tennis racket here, but anyway, it’s behind me.

I plotted our portfolio in terms of tennis players, and this is very nerdy and forgive me for that.

I love nerds. I love them. I think nerds are important and I’m very nerdy in my things. With the risk of being nerdy, I would describe the tech world as the, we don’t invest in the Nadals and the Federers and the Djokovic’s.

They are the Amazons and they are established and very large. We invest in the very young players and sometimes these young players grow up to the extent. Babylon still has a leader in its field for where it’s playing, but it’s not reached its full potential.

This is like the German player, Alexander Zverev, for example, he’s one of the best in the world, but there’s much more potential. He will be number one in the world. I’m quite sure. And the same goes for; Tzitzit pass and Dimitri Medvedev. But then also in the portfolio, we have the stuff that’s in the shadows today of all the methods in our portfolio, the Babylons, we have companies like Swivel, Dosta Vista, and Booksy, which, we don’t hear about them much.

You could compare these to some of the younger players, like Corda for example, or John Nexin. But then we also have very young players, people who are kids basically and those are the zero point ones in the portfolio. There’s this risk with them, maybe they don’t make it to the top of the world, but, if they do there are lots of potentials.

VNV Global’s next-gen stars

[00:54:49] Tilman Versch: What do you like about these next-gen stars compared to Dosta Vista, Booksy and what do you like about them and what made you invest in them?

[00:55:03] Per Brilioth: Well, first and foremost, we have three that we call the next-gen right? It`s Dosta Vista, Booksy, and Swivel. All three of them, very much enjoy the potential of network effects. One more user makes their product a little bit better and that attracts more and they all have that. I mean, the swivel is essentially a bus platform for large emerging market cities.

Booksy is a marketplace for the beauty industry, which is larger than the food industry. And then Dosta Vista is a marketplace for last-mile delivery. So, all of that, and very strong founders. Dosta Vista is Russian, Booksy is run by a Polish guy who now lives in America, is very focused on America. And Swivel I think is run by perhaps the strongest tech entrepreneur from the Middle East that we have today, Mustafa Candel. They’re very strong and they’re going after enormous markets.

Strong founders

[00:56:15] Tilman Versch: What makes these people strong in your definition?

[00:56:21] Per Brilioth: They are like we talked about before. They’re very passionate about what they do to the extent that they have a lot of patience and this is what they do in life. I mean, as you and I spoke about they`re perhaps nerds about what they do, they’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this and they’re very, very focused on it. But then they also don’t have pride in that negative way that if the ship is going this way, and even though it might be better to go that way, I’m still gonna keep it this way. So they say like, “ah, this was wrong, we have to go that way to succeed” and they will.

So, they are humble. I think in that way, which I think is super important.

The role of data

[00:57:12] Tilman Versch: How much does data play a role in the decision-making of these people and all investments in your portfolio?

[00:57:22] Per Brilioth: I think that’s a very common denominator. I think all companies we have are all tech decisions based on data, they’re data-driven. Very, very data-driven.

Established players in the portfolio

[00:57:32] Tilman Versch: That’s good to know.

When you think about the established players, you already mentioned why in Babylon. What is the interesting thing about why there might be the public image of some of the viewers that is just as good ascending around the corner and they are trashing the inner cities, but what is in your eyes interesting and why?

[00:57:59] Per Brilioth: Well, from our perspective of investing, what’s interesting is that they possess this concept of network effects that`s not here. It’s more difficult to see maybe, but it’s quite simple in that you will not take a void or a tear or a, whatever it is if it’s not outside your door. If it’s five blocks away, if it’s 500 meters away, you will go about your travel like you did before these things were present. The only reason it can be outside your door is if I have taken it there to come and visit someone in your building or visit you. And so the one who has the most users will have its scooters most spread throughout the city. And if they are more spread so that they are outside your door, you will have more users and more users will make them more spread.

So, it’s very clear that Void is a leader in pretty much all the markets that they’re in and here, it’s very clear that they have a certain amount of scooters percentage-wise, but they have a larger percentage of the revenue. So, they have a lot of percentage of the scooters. For every new scooter, they put out the revenue goes up on all the other scooters they already have out. I think that’s the from our asset, for me, as an investor in investing, in what we look to invest into what we do, that they very clearly click check that box.

But then, I think also the revelation there is then how popular this has become both from consumers, but also city councils. People want to move around the city with fewer and fewer cars and the city councils, because their voters want it, want to reduce the number of cars inside the city. This fits very well into that, and, of course, it’s the most efficient means of transportation in terms of the environment. The only thing that is better is the Metro. But what this gives you that the Metro doesn`t is that it gets you from point to point, right?

It’s not a station to station. It gets your point to point and I think is very attractive for people. This has become infrastructure. I didn’t understand this when we started it but now it’s infrastructure, it’s an infrastructure that’s licensed in the same way as maybe as the toll bridges are licensed, which has made it also quite interesting. If you think that at the initial point of this would be owned by the Ubers of this world, I think it could be owned by the same people who own a toll bridge infrastructure.

Babylon Health

[01:00:50] Tilman Versch: Will Babylon also become infrastructure? Where do you see the trajectory there?

[01:00:57] Per Brilioth: Yeah in some way you could describe it like that, but it’s not as clear as it is with the Void. But, what I think is very clear is that we all agree upon that the health space, I guess, is the last very, very large sector that is yet to digitalize.

I mean, the online penetration of primary care today is reminiscent of e-commerce in 2000. It`s 1%. I think it’s going to be a hundred percent, over time. It’s a very large space but I think it’s the visibility again, into exactly what is very, it’s not super high. You have to back adaptable players and you have to back players that digitalize this properly because also it’s very expensive, the healthcare system in all our societies right? The kind of countries you and I come from, but also in the US it’s even more expensive.

You have 80% of the costs here in some way from employees, so to make this more affordable for people you have to properly digitalize it. Babylon is the leader so I think it will become the heart of many health systems in the world and in that way, maybe you could call it the infrastructure, but there are some different aspects to it.

What makes Babylon the leader?

[01:02:30] Tilman Versch: What makes them the leader?

[01:02:33] Per Brilioth: Well, there is no one who has applied this concept of AI to the extent that they have, and also no one has been able to sell an AI-based product to the same amount of clients and very large institutions. Their customers are the National Health Service in the UK, Tell us in Canada Prudential, and Dean, Bill Gates Foundation. These are all institutions and companies that are able to understand very clearly what’s the best product out there.

They are able to, become a customer of the best supplier out there. Bill Gates, Prudential, they’re a world-class institution and they’ve all chosen Babylon and they’ve all chosen to extend their relationship with Babylon. So, I think that there’s no one else who’s done that with this pure digital product at the heart of the business.

[01:03:36] Tilman Versch: Isn’t that super hard because healthcare is such a national thing?

[01:03:42] Per Brilioth: It is hard but if you want to fix the simple things, that’s easy. This is hard, but it also means that the upside is large.

Babylon in 3-5 years

[01:03:59] Tilman Versch: It is. Where do you see Babylon in like three or five years?

[01:04:06] Per Brilioth: Well, I think, they will still be building their products. I mean, this is a company that built products for five years before they had the first customer. They will still be spending lots of investments on continuing to refine their product because even in three, four, or five years, we’re not going to reach the end game of this, right?

In that number of years, we’ll look back to them, they will be a multi-billion Euro revenue company. And so they’ll have proven that this works and this is in demand. I mean, they already today have large revenues, but in that number of years, they’ll be much larger. I think it will be very US-centric. The US has of course a very broken healthcare system and one that needs a lot of attention. So, when it’s very large, it’s natural for the company to focus there and they’re focusing there. So we’ll probably call it an American company in terms of their markets, but it will be based out of Europe. I also think it will be listed in that certainly in that number of years. So, listed company, multi-billion dollar revenue, very US-centric.

Will VNV Global still be a shareholder in Babylon in 3-5 Years?

[01:05:33] Tilman Versch: How high is the chance that you’re still being on the side of Babylon then as an active shareholder?

[01:05:42] Per Brilioth: I think it’s quite high, I think it will be listed. It will be a very large company. I think it will be a $20 billion-plus sort of market value company. I think at that point in time, there is a risk that we may have distributed the shares to the shareholders but I’ll keep mine.

New areas of investment for VNV Global

[01:06:03] Tilman Versch: We will see how it plays out. Going a bit further up with the outlook or going away from Babylon, which areas of new investment opportunities are you currently gravitating to, where you find interesting ideas, optionalities, you want to go deeper into it?

[01:06:29] Per Brilioth: We invest bottom-up. We look for these three things for that. We will continue to come back to it; network effects, large markets, and a lot of good strong founders. But that has led us to three sorts of big macro themes classifieds where it was, where we started. We still have some of that classified/marketplaces, but then we have a lot of stuff going on and mobility, which is a strong macro theme in itself that we’ve touched upon, right. With cities becoming non-cars and that macro team drives the large market, but, hand on the heart, it’s the network effects company that we’ve been looking for and that has led us into that market.

The same goes for digital health. I mean, digital health is so it’s just something that’s a macro theme that’s so strong and it`s been accelerated enormously by COVID. But that’s going to continue for a long time, but we are there because we found companies that can build very high barriers to entry. But if one allows oneself to sort of expand what we see today, that there are more and more opportunities that we look to which are in the intersection of these network effects and a macro that has to be described as a climate macro. We have very fascinating opportunities around food waste, Agri tech, the way consumers are looking to sort of source stuff locally, and market places around that, some of them we are already exposed to, but there’s an increasing amount of activity there. So that may be a description of the new theme if you will.

Climate and network effects

[01:08:28] Tilman Versch: Where do you see there the network effects coming in on the relation to climate or efficiency?

[01:08:35] Per Brilioth: Well, food waste, for example, there’s a marketplace for food waste that we are very excited about. So that’s a marketplace, right? Fragmented demand, fragmented supply, lots of liquidity in the middle.

[01:08:55] Tilman Versch: 30% of the food is wasted or something like this.

[01:08:56] Per Brilioth: Yeah, no it’s a horrible amount of food that’s wasted in the world that we have to fix, it’s very, as part of, us being, taking care of this planet better. But beyond that, I think we see a lot of data place around agriculture which are perhaps, global niches, small niches, but on a global scale, they become large. Here it’s sort of, the network effects come around the same way as Babylon. For example, not the one who has the most data will win here.

That’s farmers will go to the company that has the most data, and then that gives them more data than you’re off in that spin. So, there’s a couple of opportunities like that, weather data, other types of data and then there are other marketplaces, like your local corner store, you go there and you probably want to buy apples from your local orchard, but your local corner store has no marketability to source that efficiently.

They can’t go out and sort of, contact all the local farmers directly. So, quite a few marketplaces are coming about, which help your local store to source local apples and still do it efficiently. So, those kinds of opportunities are very interesting, too.

VNV Global in 5 years

[01:10:23] Tilman Versch: That`s quite interesting. Looking five years out, where do you see VNV global then? And might there be a chance that you have another name, or are you staying with VNV global?

[01:10:33] Per Brilioth: No, I think VNV global is where we will stick. We decided to drop the Russian-sounding Vostok, not because we don’t like Russia or like investing in Russia. But because we had so little in Russia, so that we sounded like we were only about Russia, but VNV global, I think is generic enough. I mean, that’s what put us in one bucket. I think we’ll do what we do today. I think in that number of years. I think in that number of years, there’ll be five, six companies that probably are in the portfolio now that are quite large in comparison to what they are today in percentages of the portfolio that will have grown up that will become top 10 in the world in terms of tennis.

There will be a lot of new ones. We started a scout program last year where we have a handful of scouts that we know very well, we trust very well and they know us very well and they’re typically entrepreneurs themselves. So, they get a lot of asks from other young entrepreneurs for help and those young entrepreneurs are always fundraising. So, if the scout decides to invest, we say, we’ll live at five to 10 next, what they invest and give them a little part of the upside for handling. So our ambition is that we will have 10 Scouts and each scout will build a portfolio of 10 companies. We’ll have a hundred very young companies in the portfolio and then, as they hopefully grow, we’ll be able to invest.

Growth in VNV Global’s team

[01:12:16] Tilman Versch: You have a very lean team. Do you see a chance a team will grow as well? Or are you going about the growth of the Scouts?

[01:12:25] Per Brilioth: Maybe the team will grow somewhat, but I think we are all much more interested, in running investments than running people. So we like this concept of using the network here. All these Scouts, for example, are people that we’ve known from portfolio companies or in the industry. And so it’s more efficient for us to use a network of people to do the work that we can’t do in-house.

[01:12:59] Tilman Versch: That’s interesting. I’m fine with my questions at this point. Do you have something to add we haven’t discussed or you think that it’s a good closing word for the interview?

Long-term investing

[01:13:12] Per Brilioth: I don’t have. Not really. I think we talked about it a lot. Your questions were very good. We are all about taking risks, right? So it’s typically a volatile journey. But I’m very focused on not taking a risk if the upside is not enormous so the risk-reward, at least, I’m very confident about is very good. And then it’s also when that’s the case, it’s good to be long-term I guess, it’s the other important factor here. You can ride out the volatility.

[01:14:04] Tilman Versch: Thank you very much for the interview and for taking the time and thank you very much for your honor listening to it. Thank you. And bye-bye.

[01:14:13] Per Brilioth: Thanks. Bye.

Disclaimer

Finally, here is the disclaimer. Please check it out as this content is no advice and no recommendation!